The Schools Transforming Immigrant Education

Schools for newcomers are trying to better meet their unique needs, but some worry they’re perpetuating segregation practices of old.

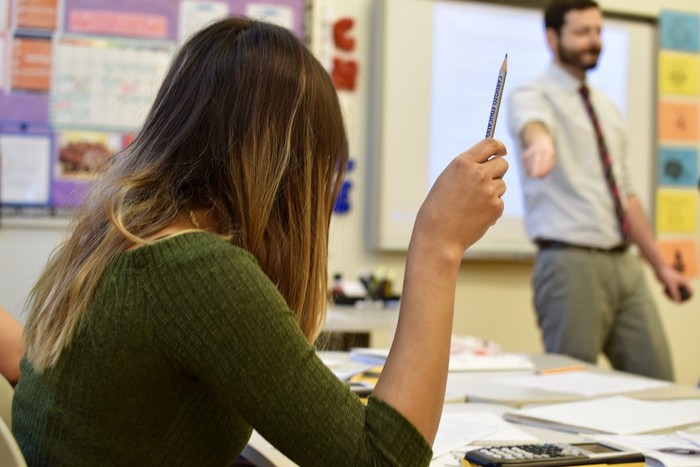

Katherine Zelaya sits in the front of her math class, leading her table of classmates in a word problem that’s asking them to determine the median and mean for a set of numbers.

“¿Por qué?” she chimes in, asking Maria Alejandra to tell her why she came to a certain conclusion.

“Jesús, termínalo,” the 19-year-old says a little later, encouraging the classmate on her left to finish his work.

The scene in Michael Krell’s probability and statistics class at the International Academy at Cardozo Education Campus in Washington, D.C. is a far cry from what Zelaya remembers of her first year in the U.S. after moving from El Salvador almost four years ago. Back then, she was in the minority of students at her former high school who were learning English.

“I knew some things that they were doing in the class, for example, in math class,” said Zelaya, who has big brown eyes, an ombre hairstyle that fades from brown to blonde, and pink braces that sometimes cause a slight lisp. “Like, I know the process and I know everything about it … just the problem was the language to communicate with the teacher and with the classmates.”

Now a senior, Zelaya is an inaugural member of Cardozo’s International Academy, a school within a school designed specifically around the needs of recently arrived immigrant students like her. She feels confident in her classes now, she said, and enjoys being able to support her classmates in their learning.

“Sometimes I know little things that probably the other students didn’t know, so I can help them and teach them some words or meanings,” she said.

Schools like Cardozo have been growing in popularity across the country in recent years as an alternative to educating newly arrived immigrant students in traditional public schools, where students who are learning English often trail their native-English-speaking peers academically and are at high risk of dropping out. The approach has taken off in the D.C. area, with the opening of five international high schools and one middle school since 2012 to meet the needs of a growing population.

Data suggest the targeted approach is working: Students in these schools outshine their English-language-learner counterparts in traditional high schools.

But the growth hasn’t been without controversy. While supporters look at these models as a way to close the achievement gap for a vulnerable student population, some critics liken the separate learning environments to segregation practices of old. The schools have also raised questions in some communities about focusing too many resources on immigrant children when the test scores and graduation rates of native-born students of color also lag behind those of their white peers.

English-language learners, or ELLs, represent 9.4 percent of the student population in U.S. public schools, according to the most recent federal data available. These students score well below their non-ELL peers on national assessments in reading and math and have a graduation rate of 65.1 percent—the second lowest after students with disabilities.

It’s those kinds of statistics that the Internationals Network for Public Schools is trying to combat through the opening of targeted programs that place ELLs on a level playing field with their peers. Most of the 8,600-plus students across the network have been in the U.S. for less than four years and score in the bottom quartile on an assessment of English proficiency when they enroll in school.

These programs aren’t just in major urban areas like D.C. and New York City, where the Internationals Network began and has 15 schools. The organization recently helped to open a school in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and school districts elsewhere, like Indianapolis, have also established similar programs independent of the network.

It’s a question frequently addressed in districts where there’s an influx of immigrants, said Annie Duguay, whose work at the Center for Applied Linguistics focuses on school-aged English-language learners. Immigration policy, population flow, regional economics and other demographics are all factors, she said.

Districts experiencing a large growth of immigrant students have been experimenting with such programs, and there is a lot of interest among content teachers, Duguay said in an email, adding that sometimes, teachers may want such a program for the wrong reasons, hoping it will “fix” a student’s English before they enter their classroom.

“A program such as Internationals is a more additive approach where there are large populations of immigrants that warrant a program and in particular for secondary students with limited or interrupted formal education who may be learning literacy and numeracy skills for the first time in a formal school setting. Programming really requires a holistic look at the demographics of the region, educational and linguistic backgrounds of the students and culturally-responsive school supports,” she continued.

Though the majority of students at Internationals Network schools are from Spanish-speaking countries, the children come from all over the world and speak close to 100 languages total—from French to Farsi. Some have little to no formal education and others are on par academically with their American peers, said Internationals Network Executive Director Joe Luft. At D.C.’s international high schools, students’ education levels and experiences fall on a particularly wide spectrum, with the city being home to children of diplomats and refugees alike, educators note.

Programs affiliated with the network vary in structure: Some, like the international academies at Cardozo and Roosevelt Senior High School in D.C. and their Alexandria, Virginia counterparts at T.C. Williams High School and Francis C. Hammond Middle School, function as schools within a traditional public school. They have separate counselors, teachers, and classrooms but the same top-level administration as their parent schools.

Other models, like International High School at Largo and International High School at Langley Park in Prince George’s County, Maryland, are entirely separate schools. Though initially launched with funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the schools will be fully supported by district funds in the upcoming school year.

No matter the model, these schools share a common goal—to enable ELL students to become proficient English speakers who are prepared for college by the time they leave high school, Luft said. The network has grown to 27 schools since its official launch in 2004, and is eyeing further expansion next school year.

“The core part of it is that the language development of our students is everyone’s responsibility,” Luft said when asked what makes network schools different. “The traditional high-school model is that you have teachers that are responsible for different subject areas and often there’s a language-development teacher or an [English-as-a-second-language] teacher … and yet none of the other instruction throughout the day is really geared towards [ELLs’] needs.”

This approach was evident during Zelaya’s probability and statistics class, as Krell, the teacher, asked students to read and write the definition of “outlier” as he introduced the math term. Midway through class, he launched into a full-blown grammar lesson on forming conditional sentences when discussing hypothetical situations—if the median were to change, for example.

According to graduation statistics in New York City, the approach seems to be working. Last year, 74 percent of graduates at network schools finished in four years, compared to 31 percent of English-language learners citywide. The network’s six-year graduation rate was also higher—78 percent compared to 49 percent.

At Cardozo, still too new to have trackable graduation data, there are early measures of success. The attendance rate at the academy has been consistently higher than the overall average attendance rate of Cardozo High School, which houses the academy.

Also part of the network’s model is an emphasis on preserving students’ home languages by allowing, and even encouraging, students to use their native language in the learning process—just like Zelaya was doing with her classmates.

“It’s a really important part of who students are, but it’s also an important part of what they can use to make meaning for learning in school,” Luft said.

For Zelaya, it’s a double-edged sword. She appreciates the opportunities to speak Spanish with her peers because she’s more comfortable communicating in her native language, she said. But at the same time, she knows they should be all be practicing their English to become fluent.

When Zelaya was 15, a local gang member running from police forced himself into her family’s home in El Salvador, she said. She remembers moving in with her grandmother for a while until her mom finally convinced the gang member to leave. But soon after, the family started receiving threatening phone calls that made them fear for their lives.

“We told my dad that, and he said that we couldn’t live in there because it was too dangerous for us,” she said. “When people say no to the [gang], they decide to kill them.”

Zelaya’s father had moved to the U.S. when she was in elementary school, and though he’d planned to return to El Salvador one day, he decided to send money for his wife and children to join him in D.C. instead, she said. The family has been seeking asylum with the U.S. government ever since.

Zelaya enrolled in Cardozo High School a month after arriving in D.C in October 2013, before the school opened the International Academy in 2014; she’d just turned 16. She didn’t speak any English at the time and was working with only one English-as-a-second-language teacher. She said some students laughed and made fun of her and the other Spanish speakers, but she tried not to let it bother her.

Even now, when she takes gym class and electives with the students at the larger Cardozo High, she feels like she doesn’t fit in.

Cardozo teachers treat the immigrant students differently, she said, and though the two schools share hallways and a cafeteria, the students don’t really mingle. (As of this article’s publication, the school’s principal was unavailable to provide comment.)

For some, that’s a problem.

When Prince George’s County announced it would open two high schools for nonnative English speakers in fall 2015, the decision was immediately criticized by some. Parents complained that the new schools would have newer resources than Largo High School, which shares a building with one of the international schools, and others in the majority-black community felt the separate learning environments sounded all too familiar. The local NAACP chapter even called officials from the organization’s state offices to weigh in.

For Barbara Dezmon, the education chair for the Maryland NAACP, the main concern was that the schools’ model did not include a plan to transition students out of the program once they become proficient in English. Long-term segregation under any circumstances is unacceptable, Dezmon said—“whether it is Largo, whether it is Harvard, or whether it is that school in Arkansas back in the 50s.”

“The plan has to be one in which these children who are coming with a need as English-language learners,” she continued, “participate for probably a year at least and then they enter the general population of the school that is part of the program.”

Gary Orfield, who co-directs the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at the University of California, Los Angeles, and conducts extensive research on school segregation, also opposes keeping English-language learners in separate environments for too long, he said. But he knows it doesn’t benefit students to put them in a classroom where they don’t understand what’s going on either.

“There’s a lot of hard choices. Many of them are being made with good intentions,” Orfield said, noting that he has not personally studied international schools but has noticed a lot of enthusiasm for them.

International High School at Largo Principal Alison Hanks-Sloan is aware of the community’s concerns, though she said support for her school has improved recently, even as she’s made more efforts to partner with the school next door. She also emphasized that the international schools in Prince George’s County are simply options that are available to students who struggle with English—students are not forced to go to Largo and can still choose their in-boundary high school if they’re looking for a bigger school with more extracurricular opportunities. And unlike most other Internationals Network schools, the ones in Prince George’s County aren’t restricted to recently arrived immigrant students; even English-language learners born in the U.S. can attend.

But as far as a plan for transitioning out of the international schools, there isn’t one.

At the International Academy at T.C. Williams in Alexandria and the academies in D.C., students can take elective classes offered by the parent high school, thereby mixing with native English speakers. But Luft said Internationals Network schools are different from other transitional ELL programs in that they’re designed to provide a full, rigorous academic curriculum; the goal isn't necessarily for students to intermix with native English speakers but rather to be immersed in an environment that's tailored to their unique needs.

It’s up to the students whether to stay or go.

Back when the Prince George’s County international schools were announced, local NAACP President Bob Ross told The Washington Post that the schools were putting the needs of newcomers “ahead of the needs of those who are already here.”

“You can’t close the achievement gap for one group and then [not] close the achievement gap for the other group,” he told me more recently.

But even though he wishes the schools had adopted a more integrated model that included both native and non-native English speakers, he’s since shifted his focus to other issues and said he hopes the schools succeed. And in today’s political climate, he wants the immigrant community to know they have an advocate in the NAACP—not an enemy.

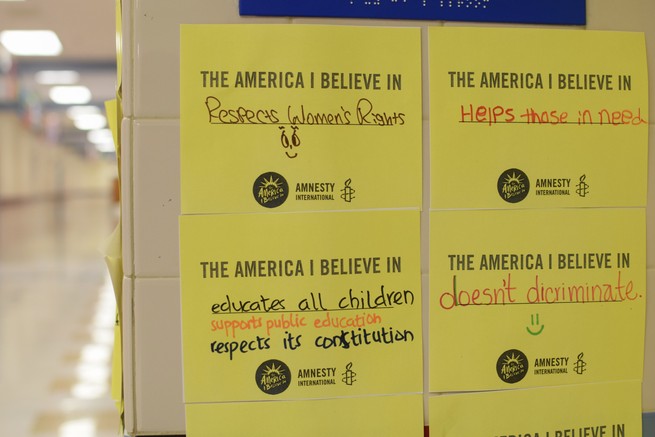

In a school full of immigrants two miles from the White House, Zelaya and her classmates have felt the ripple effects of a new president’s controversial immigration policies that pledge to put Americans first.

She has always loved school but has sometimes wondered since coming to the U.S. whether it’s worth finishing; in her opinion, finding a professional job can be especially difficult for immigrants.

Some people “think that we can’t work, we can’t do anything good for this country,” she said. “I feel kind of angry sometimes because I feel like [those people] look at me less. It’s difficult for us even to find a job, even to work, [to go to] school ... everything.”

Ultimately, it’s Zelaya’s after-school job at Popeyes that keeps her motivated. She wants to continue to learn English so that she can go to college and work toward a better life for her family.

“While I’m working at the restaurant, I tell myself I don’t want to be here all my life,” she said. “So I tell myself you have to study, you have to prepare yourself to have a better future or better job in your life.”

She was recently offered scholarships to attend Marymount University, Hilbert College, and Catholic University, but plans to give the University of the District of Columbia a try before possibly transferring. She plans on studying education.

Could she have learned in English in a regular school setting? Yes, Zelaya said—in her own way. But she prefers the focused attention on language development and extra support that she’s received at the International Academy. Besides that, she said, she feels like she’s found a new family in her fellow immigrant peers.

The students all come from different backgrounds, yet share a bond in their common experiences—like working after school to support their families and going to school every day to try their best, she said. “I can tell them what I feel—anything. I can tell anything to them because I know they will understand me.”