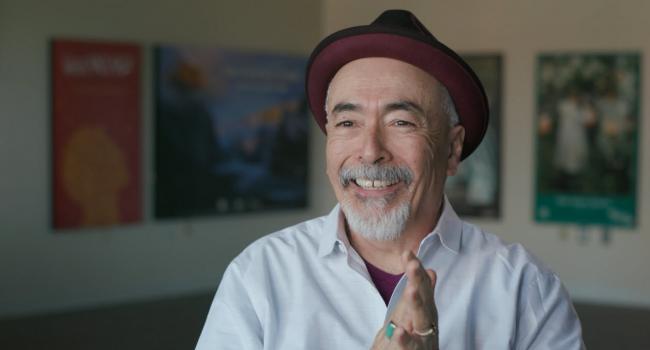

Juan Felipe Herrera

Juan Felipe Herrera is a poet who served as the nation's 21st Poet Laureate. The son of migrant workers, Mr. Herrera says that he was always moving in his childhood and that his mother in particular bestowed upon him a great love of language and folklore. In this special in-depth interview with Colorín Colorado, Mr. Herrera shares memories of his childhood adventures (and romances) and remembers Mrs. Sampson, the third-grade teacher who had such a profound impact on him and "turned him towards the land of poetry." Mrs. Sampson was in the audience at his inaugural reading as U.S. Poet Laureate, which you can read more about in the articles below. He also talks about the dynamic environment at UCLA in the 1960s that inspired so much of his creativity, and he shares some of his favorite poetry activities for students.

Related Resources

- Resource Collection: Juan Felipe Herrera (Library of Congress)

- Poet Laureate's Defining Moment (San Diego Union Tribune)

- New U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera Made a Fantastic Debut in DC (The Washington Post)

Video Interviews

Transcript

Juan Felipe Herrera: Memories from Childhood

The house my father built on a truck

My father was 66 when I was born, and my mother was around 40 or 41 when I was born. And I was born in Fowler, California, which is in the San Joaquin Valley, the central valley of California, farm worker agricultural belt.

So my father was always a farm worker, since day one. He jumped on a train from Chihuahua at the age of 14, probably in the late 1800s, and he ended up in Denver, Colorado, for sure. And I have a photograph of him in 1904 standing next to his friend Jose Barrera in a suit, you know, a suit. He probably purchased it at Sears, because that's where they sold those suits when I looked in an almanac from 1907.

So those are kind of the early journeys of my family that came together. And then I was born in 1948 in Fowler. So I traveled with my mother and father, I'm an only child, on a house made out of wood, one room on top of a chassis that my father found on a hill.

And that's how – that's what he did. He built it. And then attached it to the giant army truck. Giant army truck. It was like four pickups. And green, the color of cucumbers. So we would travel like that in kind of a handmade house in an amazing truck. My father always used to do caravans and carriages, because that was his cultural experience from the early 1900s. And he used to have a caravan of family, and they would travel around Texas to different cities and ended up in el Nuevo Mexico (New Mexico), in his early life, way before I was born.

My mother's photograph album

My mother came from D.F., Mexico City, with my grandmother, Juanita, who I'm named after, at the tail of the Mexican Revolution to catch up with the brothers that already were in Juarez. And were about to enlist in the Army in Fort Bliss, El Paso, Texas.

She kept an album that she bought at probably Woolworth's or Kress, those five-and-dime stores of the fifties, and in that album she put all the other photographs she had gathered from my Abuelita Juanita, who received all the photographs from all the children, because that's what you do, especially in those times.

You give the photographs of the family. It's an anniversary. It's the birth of a baby. "Here I am at the Army. This is me, for you, mom, Juanita, Mama Juanita."; So she received all – my mother received all those photos when my grandmother died in 1940. And then I received that album. Well, I learned with that album since I was a child.

"This is your grandmother. Her name is Juanita. And this is your tía, Leila Aurelia. And here's a photo of us at the border at the customs, and this is a photo they took of us before we were able to cross," and they're all dressed in black, and they look – have an interesting look on their face. It's not a happy look.

It's not a sad look. But it's kind of a look of crossing, that look we get when we cross, are being investigated and then questioned and then maybe we'll cross. I guess a look of potential. So I had all those stories, all those photos, so that's how I grew up. Always moving, always moving, always.

The outdoor world is the largest part of me

My father working tractors and planting and – or taking care of people's crops. Small people, too, with small crops, in a sense. Not that they were small people, but they were small families trying to make a living, and they happened to have half an acre. So my father would do that, and we would park in their – on their terrain, and I would goof around and play with their children. I helped my father water the crops or plant corn. So that's my early life. That's my childhood.

It's a very different world than the city world, and I'm highly moved by that world. It's perhaps the largest part of me, is – are those early years out in the open, seeing my father make things with his hands, shoes and the house, and my mother would get chickens like the – ssssshhh, ppppwwhoo, and then boil the chicken, pull out its feathers and have food or make salsa, a very beautiful fragrance. And cook and then work hard.

My toys were ants, chickens, and roosters

My toys were ants, chickens, roosters – but they would chase me. Not a cool toy. And jump on my back and peck, peck my back. Very unique animal, the rooster. And pigs and little beetles and dirt and mud. And my – I received a cowboy outfit from my Tío Beto.

I had chaps, chaparreras. I had a chaleco, a vest. And I looked like a little cowboy. And I had boots. I had botas de vaquero. And so that was interesting. And a bicycle that I tore apart to see what it was made out of. I could have put it back together, but it was a – it was a – it wasn't my kind of project. I was into tearing it apart.

And I learned Spanish from a primer from the 1800s that my mother found at the secondhand store, la segunda in Escondido, and it was great because my mother taught me how to read in Spanish with that primer, all the letters and how to read and pronounce them.

And, you know, to visualize them and know them and put them together, how to make words and stories. So that's – those are the early years. Of course they were hard years, but it wasn't hard for me because I was being taken care of. And it was cozy. And it was fun to travel, except when I had to leave a little dog behind that my friends had.

Like Rowdy the hound.

The verbal art studio my mother created for me

My mother loved riddles, songs, proverbs and sayings. She knew them from her life growing up as a girl in Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico, and in El Paso, Texas, in the borderlands. And in the borderlands, there's a lot of creative language use, and in those early days of the early 1900s, that's what everybody used if you lived in the barrio, particularly in El Segundo Barrio of El Paso. Because it's people talk, you know? It's not academic talk. It's the way the people talk and the way the people learn and the way the people share wisdom in a very kind of informal manner.

So as I was growing up, my mother used all those things and said riddles every five seconds, and she wanted to say them to me as an only child. She wanted to teach me. Just have fun with me, you know? Have fun with me. So she said, Fui al mercado y compré bellas, vine a la casa y lloré con ellas," "I went to the marketplace, I bought beautifuls, I came home, and I cried with them." And ellas y bellas rhyme. "Them" and "beautiful," those two words, rhyme in Spanish. So then I would hear rhymes every day, and I would have to figure out what the riddle was about.

Because she didn't tell me what it was about, because you have to find it. It's a riddle. You have to find the hidden entity, the hidden meaning and all those amazing things that are very complex, yet sound very simple when you say the riddle. So from a very early age, I was just deciphering, deciphering, deciphering, uncovering, untangling, finding, finding, finding the meaning of a statement through riddles.

And cuentos – she was a master storyteller, a master cuentera, first of all because she wanted to teach me many things. She wanted to impart in me her story, her life story, and all the stories of the family. It was a natural thing for her to do. She was kind of a natural-born teacher. She would have gone on in her education beyond third grade, but she would have been a fabulous, magnificent maestra, beyond that. A great teacher.

So I received all this with a channel of tenderness. And so my imagination was constantly, daily being enriched, nonstop until – probably until she passed away at the age of 80. It never stopped.

So by the time – and with photographs. And a guitar. I finally ended up getting a guitar. She suggested, "Why don't you get a guitar?" She always wanted to play guitar. So in a way – "I'd like you to play the guitar." So I played the guitar. So I got a six-string – a six-string Stella, black with a gold burst in the middle, for $20. So then I would sing the corridos that she had taught me from an early age.

That's a major force in my formation as a poet, as a speaker, as a thinker and as a person that loves language and is able to uncover it and find what's beneath it and to rearrange it and to hear it and to look at it all at the same time, and to read it and to play with it, rrrr, to really play. It's really art. A human art. So yeah, so my early childhood into my teen years was all daily instruction in the art studio, verbal art studio that my mother created for me.

The importance of passing down folklore

My mother presented a great treasury of material for me. You know, I guess you could call it el folklor, the folklore of the people, the verbal art of the people, which is very, extremely important – let’s see if I can put it that way – for our parents to present to their – to our children. If we just let the children grow up and do not present all this rich folklore that we have already, our children will miss a lot.

The famous first day of first grade

The famous first day and the famous first grade. Well, my father was the one who dropped me off in his giant army truck, and I had my big paper bag, probably a Safeway bag or a store bag, brown paper, and I had I think two burritos de papa, two potato burritos, which are some of the best burritos you can have.

And my father really literally just pointed to the school. "Allí está tu escuela. There's your school." So I looked at the building. I didn't know what it was. I opened the door. Big, giant door. I shut the door with my brown bag with two burritos. And I looked at it. I go – was nobody outside. Just a building. Big, giant cement building. Central Elementary in Escondido, California. 1955.

I walked up across the street. I walked up to the – I walked up the stairs. I opened a big door, a big, wooden, heavy door. I opened it. There was a big, dark hallway. "Okay. All right. It's a dark hallway. Okay, I guess I have to walk into it. Close the door. And there's a class I have to go into, I suppose. I have to open a door here."; So I opened the first one. And I opened that door, and it was dark. It was a giant room with a green chalkboard on the right, a black chalkboard on the right, and way ahead of me, in a corner of the room, was the teacher with a group of her students around her, I think sitting on the floor.

"I guess I have to go over there."; So I started speaking in Spanish. By the time I got there, the first contact I had with my teacher was to be spanked. She put me over her knee, and she spanked me, because I was late, because I didn't know what was going on, and because I spoke Spanish.

So then, you know, being a very, you know, chipilato boy – I was a mama's boy – I just – all I could do was cry. I just cried. Very – I'm a very sensitive guy, to this very day, which is good, because that way I can relate to people and I can write and express myself.

So I started crying, you know? I started to cry. So, okay. So I guess my tears dried up. And it was time for something, because the bell rang. So I got my bag and I went out there and I ran and I opened the bag and I started eating, but I looked out and everybody was playing. "Oh, gosh. I'm the only one eating here. Okay. All right. I think I got it.";

Bell rang. I went back to class. And we did some kind of work, and the bell rang again. I was prepared. So I left my second burrito there and I ran out the door and wanted to play, but everybody was eating. So that's just the way it was. You know, that's what happens to us when we only speak Spanish and we don't know about the school and we go in and we try to figure things out by ourselves, which is the experience of our children, even to this very day, that speak only in Spanish.

So that was my first day, and I went home, and I didn't tell my mother what happened, because it was a different world, a different planet. So "Cómo te fue?"; I said – she must have said, "How are you?" And I probably said, "Okay." But my – but my mother could read me, could read right through me, so I'm sure she figured out how I was feeling.

Or what had taken place. And I never forgot that, you know? So from that day on, I kind of held back. I held back. "I – well, I don't really know English that well, or I don't know it at all, and I was spanked and hurt, so I'm going to kind of cool out."; So I began to just withdraw immediately.

Photograph day in first grade

Then there was a photography day. You stand up in first grade and you look out into the camera, and they take your first-grade picture. So I used that on my – on a book of children's – my first children's book. It's the same me wearing the same clothes, a plaid shirt and jeans, making the same face with my short, buzzed-off hair and with a chalkboard behind me, looking into the camera.

So I use that photograph, just like my mother had used photographs for me telling me stories. I use my photograph. And my mother's photograph is at the top, from 1936. On the cover of the book for children. So I also love to do that, is to bring out things that I have and show them to the reader so the reader can think about that, too, about photographs, parents, family. And their first-grade picture.

Romance and punishment in first and second grade

I remember Valentine's Day, when I got a little card from Carolyn Centers. And it said, "I," then a second word, then the third word was "you." I go, okay, I know the word "I." I know that one. And I know "you." But this one in the middle is interesting. I have a feeling I know what it is, but I want to double-check. So I shouted to my friend, "Hey, Miguel, what's this word? I think I know what it is, but I don't really believe it, so it must be – it's a weird word, I think. What does it say?"

"Oh," he says, "'I love you, Juanito.' She loves you." Carolyn! I was very pleased. I had a girlfriend, but – I couldn't – I couldn't – I couldn't move on it. There was no way I was going to do anything about it or say anything to her or write anything to her. It was just a good thing. It was going to be a long-distance romantic relationship. So that was Valentine's Day. So things were positive also in that classroom.

And there was Halloween. I remember running home, because I knew my mom had bought a bag of those chewy saltwater orange toffee things, Halloween things, so I couldn't wait to go to school – to go home at the end of that Halloween day. So that was cool.

So first grade was like that. It was tough to step into, and it was also joyful on occasions, and I made it through, but then the second grade it was another city. I had to start over. Which was equally difficult and brutal in some ways, because some of the students would get sent back to the cloak room with bloody noses, and they just – they were just – bloody noses would drip to a pool on the cloak room, which was hidden from the main classroom.

And I forgot if the teacher had slapped that student or they just got a bloody nose and got sent to that room, to the cloak room. The cloak room was our little prison in second grade. We would write our names. X, you know, X, two times. You go three Xs, how many times you served in the cloak room, and I went back there myself. And that's just the way it was. Yay for second grade. It was difficult. It was difficult. This was in the barrio of Logan Heights, San Diego, California, in 1956. And that's when I met Mrs. Sampson. Which is another story.

The day Mrs. Sampson told me I had a beautiful voice

After I went to second grade in Burbank Elementary in 1956 in San Diego in Logan Heights barrio, it was the wrong school, apparently, because we had moved again, since my father loved moving. It was in his blood. So we moved further out of Logan Heights, close to the edge of it, and then the principal said, "Well, you know, you're not supposed to be in this school anymore. You already moved. So we're going to take you to Lowell Elementary."

"Oh, okay."; So they put me in a car, and there I was, you know, going in the car, to Lowell Elementary, and got off the car. He took me into the main office. "Well, here we have Juanito Herrera, and he lives on National, right here, a block from here, so let's sign him up and put him in class, into third grade." So that's when I met Mrs. Sampson, Mrs. Lelya Sampson, who was a master teacher, and she loved her students.

So one day she said, after she'd played a lot of gospel music on the giant phonograph, "Juan, can you please come up to front – to the front of the class? I want you to sing a song." And I was shocked. I was shocked. I don't – no one had ever called me up first grade or second grade, number one, and no one had ever invited me to the front of the class, number two. And no one had ever called me up and invited me to the front of the class to sing, because I was a non-speaker. I went from being a Spanish speaker to an almost-English speaker to a non-speaker, because I had learned not to speak up in class. That Spanish was not to be used, and English – if you could use it, you better use it in a very specific way. And that's it. So I wasn't about to speak.

And she said, "Could you come up and sing a song?" That's beyond speaking. I go, "Oh God, I don't think"; – so I was shocked, was electrified. So I walked up, because she was so kind, and so she knew – she knew how to invite a student. All right. I made it to the front of the class. And she was standing next to me. Which is – was excellent. I wasn't alone. Good. I had – I had a – she was supporting me. Excellent. "That's – I can do this a little bit,"; I thought.

"Whenever you want to sing a song, okay?" "All right." "What would you like to sing?" "I want to sing 'Three Blind Mice.'" "Okay. Excellent. Excellent. Okay, here we go. Whenever you're ready." "Okay. Three blind mice. Three blind mice." And I finished the song. And then she turned around to me and she said, "You have a beautiful voice. You have a beautiful voice. Did you know that?" "No. I didn't know that. As a matter of fact, I don't know it right now. Even after you said it."; And I turned to one of my friends. I said, "¿Qué dijo?" "What did she tell me?" I think I knew what it was, but I didn't want to believe it.

I definitely didn't want to believe it. I wasn't going to believe it, and I must not believe it. "What did she say?" "Que tienes una voz muy beautiful, muy bonita. "You have a very beautiful voice." "Oh, I do? Well, I think I'm going to go back to where I was."; And I went back into the invisible role where I love to be.

But that moment was a defining moment for the rest of my life. That's when she literally picked me up and turned me towards the land of poetry, the land of speaking, the land of creative expression and the land of liberating myself with the real self that I was given. So that's Mrs. Lelya Sampson. Major, major force and teacher in my life.

And that's why I'm here. And that's why I'm a Poet Laureate of the United States, and that's why I go around throughout the whole nation saying the same thing to everybody that I meet. I'm still – I give to everyone what she gave to me.

I became a non-speaker

I was a non-speaker. I went from being a Spanish speaker to an almost-English speaker to a non-speaker, because I had learned not to speak up in class. That Spanish was not to be used, and English – if you could use it, you better use it in a very specific way. And that's it. So I wasn't about to speak.

Logan Heights barrio

I went to second grade in Burbank Elementary in 1956 in San Diego in Logan Heights barrio, which was a quaint – for me, at that time, a beautiful barrio. We were all – everybody was – didn't have any resources, of course. Everyone was living on tortillas and chiles and frijoles and working in the canneries or just surviving in that barrio.

So when I say "barrio,"; it's not like a brutal barrio, but it's a barrio of mostly Mexicanos and African Americans in San Diego, not that far from downtown San Diego, California, in the mid-fifties. And had this panadería, this little Mexican bakery. This little movie house, El Coronet. There was this – which was about good for maybe 75 people. And beautiful little shops and restaurants, Las cuatro milpas.

I guess you wear a tuxedo when you recite a poem

I was in sixth grade in San Francisco, California, in the Mission District, living with my mom in a very small apartment. I was at Patrick Henry Elementary School, and we were to write a report on a particular geographic item or do something optional – I think. Yeah.

So I said, "I don't want to – I don't want to do a report on the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. I want to recite a poem by heart. One of my mother's poems." And she had a poem called, "Underneath the Old Apple Tree." "I want to do that."

So I learned it. Practiced it. And then I got stuck on a particular thing. "I have to wear a tuxedo." I guess you wear a tuxedo when you recite a poem. Okay. So I had to go downtown to look at a tuxedo shop. So I found a tuxedo shop on Market and Van Ness on the corner.

But I didn't want to go right into it. I wanted to examine it from far away to see if it was feasible. So I was across the street from the tuxedo shop with my X-ray vision, peering into the shop, because it kind of was a big thing to do. I had $10 that my mother gave me to rent a tuxedo.

In my mind, it was – that's what I wanted to do. But after a while of standing there I go, "I don't think so. This is too complicated. I don't – it's getting too emotional for me to go in there and put $10 on a tuxedo, and sounds complicated. So you know what? I'm not going to read the poem. I want to go back home, go back, do the report on the Bay of Fundy, get onstage in front of the audience and talk about the 60-foot waves in Nova Scotia on the Bay of Fundy, and they're very big waves. Thank you very much."

So that's what I did. I wasn't satisfied. But that's my first big experience with reading poetry, trying to get dressed up for poetry, with a tuxedo, in San Francisco, for my sixth-grade class. I was around 11 years old. Eleven years old. But I had it in mind, that's what I wanted to do. But it didn't happen. I wasn't ready yet. It was going to happen a few years later.

I decided I wanted to speak up

In seventh grade, Mr. Schuster – I love music – and I was doing great in that class, and he invited me to be in band, which was a dream, to be in band, to be in band. I wanted to play the saxophone. I put five dollars down again on a pawn shop saxophone, a tenor sax, beautiful, burgundy case, beautiful, magic. Magic. I went into the store. This time, I made it into the store by myself. I did it.

And I told the man way up here at the counter, I said, "I would like to rent – I would like to buy that tenor saxophone outside." "Is that right, young man?" I go, "Yes." "Well, it costs $250." "I understand. I have five dollars." "Ah. Okay. Let's take the five dollars. Just fill out this form." "Yes, sir." I filled out my name, the address, 11th Street – 11th and C Street, Apartment #9. "Okay. Very good, young man. Make sure you make your next payment on this day next month." "Yes, sir." Because I wanted to play that sax.

However, Mr. Schuster said, "What are you?" In class. "What am I? Oh, no."; (Exhales.) "I'm a – I'm a, uh – I'm a, uh – I'm a Hawaiian." I knew I wasn't a Hawaiian. I had been with Hawaiians. My friends in San Francisco in school. Honolulu. Nypel, Tyrona, Kina, Fredo, Bautista. I wasn't able to say Mexican.

And I sat back down, and I said, "I'm not lying anymore. I'm not going to be nervous anymore. I'm not going to be afraid anymore. And I'm not going to go in band. Because in band, I want to hide and hide behind the saxophone. I'll be able to blow and all that maybe play it, but I'm not going to be able to speak up. So I want to speak up. So I'm not going to take band. I'm going to go into chorus. I don't want to go into chorus. That's the last class I would ever go into. But I'm going to go into that class so I can be picked on, called on, asked to sing in front of everybody with my voice, which, right now, doesn't really exist. And Mrs. Sampson said it was a beautiful voice, and I want to have a beautiful voice, and I want to be able to express it. So I'm not going to go into band. I'm going to drop that saxophone dream. I'm not going to pay the next five dollars. So here I go."

So I took choir year after year after year after year. I was on a singing stage in front of the high schools with the choir and in quartets. So I was beginning to know what a stage was and what it was to be in front of very big audiences and microphones dressed up and with robes on, traveling, touring with the choir and singing in French and Italian and English and speaking representing the choir.

Mr. Harrison again said, "John-John, I want you to introduce the choir." "Oh, God. Why do you always – people pick on me all the time?" "Okay, yes, Mr. Harrison." "And I want you to do it in Spanish." "In Spanish?" "Yes, because we're going to present at the El Cortez Hotel, and we're going to present this to – some of our songs to a group of – from the Latino community, from the Mexican community, businesspeople."

"Okay, okay, Mr. Harrison, okay. Okay." "Aquí estamos con el coro hoy. Vamos a presenter cancionces de la navidad. Y es un coro dirigido por el Señor Ezra Maxwell." "We're going to present this choir, songs, Christmas songs that we've practiced and are going to provide today to you with our voices and directed by Mr. Ezra Harrison Maxwell. Muchas gracias. Thank you very much."

Wow, that was heavy-duty. So then I stepped back. So I – my teachers constantly confronted me or presented something to me that was much bigger that I had to engage with, a bigger question, a bigger stage, using Spanish and English and my voice, and so literally, since I was born, everything that happened that I faced was preparations, preparations, preparations, challenges to speak, to use my voice, to create, to sing, to figure words out and to project to audiences in bigger and bigger stages, in bigger stages, until this year. But it started step by step.

Juan Felipe Herrera: A Self-Made Poet / The UCLA Years

Reciting poetry to girls on the bus

By the time I was in – maybe I was 16, I began to recite poetry very softly to girls who were in the front seat of the choir bus. I was in the back seat. And I would recite it to them in between the seats. But at least I was saying something that I had written or songs that I had wrote and played. So I was half a step ahead. I mean, it – they were little half-steps. They weren't giant steps. Half-steps. But I was writing my songs, writing my poems and whispering them to Cindy Garrison in particular, who was a soprano. She had beautiful, long, dark brown hair and a very mysterious look in her eyes, which I really liked. But that is – that's as far as I got. And I used to give her songs and poems. So that was when I was sixteen.

Jazz in 1950s San Francisco

When I lived in San Francisco, the Mission District, we would visit my cousins and my Tío Roberto and my Tía Alvina. They had a very big Victorian and a lot of children, so I had a lot of cousins, and I slept and stayed for a year with them, and my mother also lived – and I don't remember where she slept.

She must have slept on the sofa. I never thought of that till right now. And so I shared a bunk bed. I was on the bottom bunk, and my other cousin, Vicente, was at the top, or maybe it was the other way around, and my cousin Tito had a full bed in a little tiny room. However, Tito was a teenager and a Chicano beatnik. Had all the jazz albums pasted on the wall, and he played them, and San Francisco was a jazz city. Yeah, Horace Silver Quintet, Cal Tjader Quintet, I don't know, Mongo Santamaria and many more. He had them all on the wall. He would play them every day. So my fourth-grade years were just – I was learning and picking up all the melodies and jazz of the fifties, which is the kind of classical jazz. It's John Coltrane, it's the big jazz giants. And my cousin beatnik Tito Quintana had crazy art on the walls. And that – I loved it. I loved all that. That was another beverage I loved, another experience I loved. So by the time I was at university, UCLA, jazz for me was a natural thing, because I would play it all the time.

Nothing was ever planned

It’s hard to describe my life experience, even though I've been describing it, because it's all been a migrant experience, so I just – I have just run into things, and they just – things just happened in those places in certain moments. I never planned any of it. Nothing. Arriving to where I'm at – nothing from day number one was ever planned.

Nothing was forecast, planned or written on paper. None of it. It was just like being a migrante, a migrant farm worker, child, family. It was just, "where are we going?"; "Well, let's go to Ramona."; "Well, why are we going to Ramona?"; "Because it has the best water, Juanito. They have the best water."; Okay. Ramona, the best water.

"Well, why are we going to San Diego?"; "They have the best climate in the whole world."; Oh, the best climate. So nothing was planned.

Going to UCLA

How I ended up at UCLA, you know – nothing was planned. I was walking in the hallway, hanging out. I think people were in class or something. I was hanging out with Oscar Foster, big basketball player, basketball star, and Mr. Weiss, Robert Weiss, Bob Weiss, my Spanish teacher.

I took Spanish because I liked it and because I wanted to get better at Spanish and because I wanted to make my grades higher, because I would probably most likely get an A, which I did with Bob Weiss, even though my early Spanish grades, Spanish I and II, were a little crunchy. But at least I got a B or B-. Because I didn't know the tenses, you know, I didn't know what they were named. It was very interesting. "Well, Juan, what are you doing in the hall?" "Oh, I'm hanging out with Oscar Foster. Oscar. Basketball." "Okay, okay, okay. Well, have you applied to UCLA? You know, you have good grades, you know? I'm your counselor, after all."

"Wow. What's going on?" "They have the EOP (Early Opportunity Program) full four-year scholarship, Juan. And, you know, you qualify. Why don't you go to Mrs. Cunningham's office and fill out that application, send it in, okay?" "Okay, okay, okay, Mr. Weiss." So I went. I filled it in. And bang, I got this big four-pound envelope, looked like a burrito. And I opened the mailbox. There's a big old burrito in there. "God, what is this?"; A big old giant envelope. I ripped it open.

And it said, "Congratulations, Juan Felipe Herrera, you have received a full four-year scholarship Equal Opportunity Grant headed by Dr. Kenneth Washington in Washington, D.C. And it's – and it's for you. And please report to UCLA Administration Office August 16th. And you know – enclosed you will find a map, your dormitory information, and everything else you need to know. Please bring luggage."

And I showed it to my mom and she was really excited about it. And not too long after that, I realized that I was never going to come back to that life, to that very close, intimate life with my mom, my mother. She also knew that was it, you know? That was it. I was going to go, move on and take off. And she was going to move on too, back to San Francisco. It was a – it was – but she didn't express that, you know? She went, "Okay, way to go." She wanted me to do that. She was held back as a young woman. She never wanted me to be held back at all. That's another big piece to my story. She would have held back, even if she would have had all those riddles and rhymes, held me back, I wouldn't have moved. But she never held me back.

Trying to find the dorm

And there I was in LA and it was so funny, because when I decided to get off the bus with my old luggage piece borrowed from Alurista, who became a great poet later on, who borrowed it from his father, who must have bought it at a segunda shop, real small one, kind of stained a mustard color with stripes, pinstripes, with my clothes, and then a cardboard box, Chicano luggage, with rope around it and pan dulce stains on it – that was my luggage to UCLA, and I got off the bus with that luggage and I started to walk, because I had the map in my mind. I thought I knew exactly where I was going, so I kept on walking.

I got tired. I put it down. I said, "Oh, this is probably the building right in front of me. Okay, there's an elevator. Okay, got to hit the elevator." I put my stuff in the elevator and I went up to the fourth floor – that's the magic number. Said, "It must be that." Doors opened, and I read the sign. It said, "Maternity Ward." I was – I was at the hospital. Said, "This is not the dorm. Okay." Then I went down, and I walked and walked and walked, and I got tired, and I slept on the main campus lawn, and in the afternoon I said, "Okay, I'm going to find it. I think it's on that hill." It was way up on a hill. Hedrick Hall. So that's how I walked into UCLA, and that's how I got to UCLA.

UCLA: Theater and collaboration

By the time I was in UCLA, this was 1967, 1968, the late sixties, and 1971 and '72. I found that I – of course I was – I loved poetry. I loved music, and I loved doing collective projects with my friends, because a choir is a collective group. It's a collective. So working in a collective was very familiar to me. And I liked working with people, and I enjoyed doing creative things with people. So I would ask my music friends that played the string bass or congas or piano or saxophone or were dancers – I said, "Come on. Let's do something. And as a matter of fact, let's – I want to read a poem and let's work together." So I did that very early on at UCLA. And then we would do I guess what we would call today spoken word with music or jazz with poetry.

I also put teatros, performance groups, together. I said, "Well, we have to do this together, and we have to represent what's taking place, not only write about it." So I put kind of multimedia theaters together, because I wanted a new kind of theater, not just the kind of agi-prop political theater.

I wanted a blend of a political theater and kind of like a magic theater, and so that's what I began to do as a poet, as an artist, and as a performance person, in the late sixties to early seventies, and it was – it was the life to have, because it was so filled with energy and creativity, spontaneity, and working with the communities.

So that's what I did for many years as – once I hit UCLA and found a place to put my poetry and myself into a role that was a positive contributing role for the communities in California, especially the working-class community.

UCLA: A crucible of creativity and activism

So there I was at UCLA, and I put little groups together, but since they were turbulent times in the world and in the university, we – all the students put – led a strike and shut the university down. The Chicano MEChA or UMAS, United Mexican American Students, Black Student Union, and Students for a Democratic Society and other groups decided to- we all decided to demand professors of color and students of color and scholarships available for everyone in that university at that time. And it wasn't being done, and of course at that time students responded directly. It wasn't, "We're going to think about it. We're going to go have a sandwich. We'll go to a great vacation. We'll come back and think about it again." I'm making a caricature.

What I'm saying is that students were very active. They were activists. So we decided to make those demands. The students – I believe the administration didn't comply, and – as far as I know immediately, so the – there was a strike, and the university was shut down. So that's the atmosphere.

Then the university opened up and made some concessions. And on the streets, there was the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations, there were United Farm Workers organizing efforts to represent and support farm workers in California, given the boycotts against various types of produce, especially grapes and lettuce. And since I was very connected to farm worker life, I for sure supported that. So then I said, "What can – how can I contribute? I'll write poetry, and I'll write it and speak it out here in the large arena of the university, in the large arenas of the community.";

So I found a place to put all those things where I – that I had learned, speaking, writing, poetry, analysis, performing, music, singing, standing in front of audiences into one thing in the late sixties at UCLA and traveling up and down California and the Southwest while I was in school, too. It kind of hurt my grades. But it was part of my life. My life already had begun to – began to come together.

UCLA was my first big step. It was a place to be. Very active, very creative.

A lot of things taking place. A lot of leaders in LA. Angela Davis was on campus. A lot of combustion in LA, a lot of music, a lot of theater. It was a time to be there. And great food for a poet.

A self-made poet

I got my BA in social anthropology. I never thought of taking a writing degree. Because I'd never heard of that. And I never took a writing class because I'd never really heard of that. Besides, I was writing already, and I never decided to take a workshop until I was 40, and I got a National Fine Arts at the University of Iowa Writers Workshop. But that was decades later.

So most of my writing comes from kind of a self-made – just like my father made our trailer, like he made his shoes, and my mother made salsa. That's the way I made poetry, you know, with people in the community.

What can you do to serve your community without having to wait or go to a school to learn something about it? Because, you know, it's your experience. You know your experience. And it's the experience of those that you know. You know their experience.

And it's the experience of your communities. And it's not too hard to know the experience of the community. It's not too hard. It's not going to be offered to you in any package. You have to just be open, listen, have conversations, be in those communities and think and analyze and work together to figure out what's important, what are the problems, what are the issues. They are saying the issues.

The community is vocal. You just need to come together face to face and listen, and then you have to ask yourself, so what is my role? How am I going to respond? Am I going to walk on and build my career? Or am I going to stop right here for a moment and offer everything I can?

So that's what I decided to do, as a writer and as a poet. There's more things you can do. You don't have to write poetry. If you're an organizer, organize. If you want to go into city politics, go into city politics. There's many choices. A teacher. A lawyer. Excellent. What I wanted to do was respond as a writer and as a poet, as a speaker, and as a person that can put ensembles together. That could visit those communities and present a scene of what's taking place for them to reflect on, and then we could have conversations.

California Poet Laureate

When I was the California poet laureate, it was like a nomination process, and you apply, fill out a pretty thick résumé. And there's a lot of careful investigation or analysis of your résumé and everything about you. That's okay. Fine, you know? No problem. And then you also get called by the – I believe the Senate – a Senate committee, and they ask you, "What are your projects? What do you – what do you want to do for California?";

And then I responded, you know, "This is what I want to do. I want to do an anti-bullying project for very young people. I'm very interested in that." I saw a photograph on the newsreel on TV about Joanna Ramos, 11-year-old in a school in the LA area, and she died after a fight after school.

And she had a very beautiful face, and beautiful 11-year-old, beautiful skin color. Very lively. I noticed everything about her as best as I could on TV. I said, "What a beautiful child. And what can I do? I have to do something. I'm going to do something. I don't know what it is. Sell cookies. I'm going to do something. You better get out of my way." And then a few days later, I got the call to be Poet Laureate of California, so that's why I said, "I want to do this project." Now, it's going to be called i-Promise Joanna, and it's a project for elementary schools to say, "I promise Joanna I'm going to stop bullying, and I'm going to talk about my experience as a person being bullied." So both things. So that was very – that was one of the things I talked about.

And so, "What else are you going to do, Mr. Herrera?" I said, "I'm going to do a unity poem, the largest unity poem in the world." "What is that again?" "I'm going to collect as many poems as I can from as many people in California on unity. I want them to focus on unity. And I'll put all those poems together, whatever they send me, one line, one word, 10 words, any language. I don't care what language it is. And I'm going to paste it all together like a giant sarape, and it's going to be the biggest and most incredible poem in the world on unity."

"Oh, that's very interesting, Mr. Herrera. Anything else you're going to do?" "Yes, I'm going to do the – a Stars of Juarez." "Oh, what on Earth is that, Senor Herrera?" I said, "I'm going to tell the story of Cuca Aguirre and Eva Aguirre, radio stars, poets. Comedians as well, on the – on the radio, and songwriters and dancers."

"Well, why is that? That's in Juarez." I said, "It's also in El Paso." "Yeah, but that's Texas. That's not California." I said, "Yes, but, you know, they were kind of root artists that then influenced everything we're doing now in California, because what took place in the thirties was a – kind of a revolution of Latina and Latino art and expression.

"Dance, music, songwriting, poetry and acting, and radio. Didn't happen anywhere else like it happened there. And it affected and was transmitted through the Southwest into what we know as zoot suit culture or Chicano culture in LA, and then it spread out."

"Oh, I see. Okay. All right. So what are you going to do about it?" "Well, I'm going to write a musical, a short musical based on their lives. No matter what level, it's going to happen. No matter what level, it's going to happen." So I wanted to do that as an offering to them.

I met them in their nineties, and I interviewed them, Eva Aguirre and Cuca Aguirre, and they told me about their lives as 16-year-olds when they broke out of their home and became radio stars. I thought, "That's a big story. I got – I have to tell it." So when I was California poet laureate, that was one of my projects.

U.S. Poet Laureate

U.S. poet laureate is a very different thing. I got called by Dr. James Billington, the head librarian of the Library of Congress, and – before June 2015, in the month of May. And he invited me – said, "Would you consider being the Poet Laureate of – of the United States?" I go, "Yes, I would." "Would you be willing to accept that role?" I go, "Yes, I would, Dr. Billington." Of course right now I'm saying it kind of just plain, but it was a very big moment, and I had to hold onto the table.

I was in Seattle teaching at the University of Washington, American ethnic studies, a couple of courses. "Yes, thank you, Dr. Billington. I do." And, "Do you have any questions?" I go, "No, I don't, Dr. Billington. I think this is about as far as I can go here at this very moment."

"Oh, well, thank you very much. We're very pleased, and we're going to be getting back to you. We're really excited about you being our Poet Laureate of the United States, so thank you very much." And then I sat back and I didn't really know what it was going to be or what it was. I knew the physical aspects of it: having an office and representing the United States. But of course I didn't know the scope and how deep and how stellar it was going to be and what I could do as a national laureate.

So that's what – that's how it began. And then it began to grown and grow and grow. You know, I had, I don't know, hundreds of interviews – Oprah, Larry King, Amy Goodman, Telemundo and Univision, on and on. Many interviews. All the papers you can imagine. LA Times. New York Times. England, Germany, around the world.

And all along, my focus was – is to talk about the experience of the Latino community and also to invite everyone to be their full creative selves. I'm still doing what Mrs. Sampson gave to me, what my mother gave to me. And to look at language and poetry in our lives as beautiful sources for something that's even bigger – that is, all our lives.

The other side is just visiting as many places as I can in the USA, and I work with workshops and different age groups and different everybody, you know, everybody. I'm happy. Las Vegas – I got the key to Las Vegas that did not open anything. For example. But it was interesting. I do have a crystal key to Las Vegas.

Juan Felipe Herrera: Teaching Poetry

A poetry clothesline

The Library of Congress, Poet Laureate, our division, and the Poetry Foundation have come together to do this project for 35 school districts. So I work with around 35 to 40 teachers. And they want to know how to teach poetry and find new ways of doing it, and I'm very happy to do that.

So we get together at the Poetry Foundation. We have a workshop.

using colored yarn across the wall – so from this wall of the classroom to that wall of the classroom, we paste it with masking tape. So all of a sudden you have these clotheslines made out of yarn. They're very colorful yarn.

Tendederos. So it's that tendedero project. And what do you do with the clotheslines made out of yarn crisscrossing the room? You put Post-Its on them. What's on those Post-Its? Words. And where do those words come from? Small groups of students.

And what are those words for? The students are going to get up, for once in their lives, from their tables, for once in their lives, and walk around the room. And what are they going to do? They're going to read those words and visit those words and get fascinated by all these yarns and feel excited because they're walking, and there's these weird yarns on the room.

So they're going to get excited about that, too. And they're going to have their own words and the words of other students. And then they take whatever words they want into their little tablet, go back to their group, and use those words to write a poem. So that's very interesting.

So as a poet laureate, it's a great thing, because then I'm getting in contact with students in 45 school districts and in 45 schools. That's a big accomplishment that I can contribute to, and hopefully it'll grow.

Poetry activity: The Lowrider Poem

I’ll match language making with an item that’s familiar. We’ll draw a lowrider. I used to work with schools in Gilroy, you know? It was very – lowriders were very popular in San Jose. San Jose had a big old lowrider thing going on. And Gilroy's close to San Jose. And it was really exciting. So I say, "Okay, let's draw – let's" – because I said, "What would you like me to draw?" I told the students, "What would you like me to draw?" "Lowrider!" "You mean like a car?" "Yeah." "Okay." So I drew a car. Okay. "Okay, so now we're going to write a poem using the shape of the car. You guys ready? Start reciting something."

El lowrider fue a la montaña. Subió a la montaña. Tenía el pelo muy largo. "He had very long hair." So I use the shape of the lowrider as the page for the students vocalizing words, improvising words, and it was a lowrider poem. I didn't talk about the rules of the poem. I didn't present a very unfamiliar subject. So the more familiar the subject is, at that time, a lowrider, and the more connected the students are to me personally –

– and the more I encourage them to just call out with their voices as a group, the more I can work as a teacher by using the words visually. As they say them, they get – they get reinforced and acknowledged with their very own words, and it's a lot of fun. They're laughing and creating. And having fun and succeeding all at one time. All together.

So I felt like I had succeeded as a teacher because I saw them succeeding as students, and I was very happy. They were very happy. And the teacher – I was visiting a classroom – was very happy. So then they either copy that on their paper or they redraw it on their paper. And then the teacher can add to it and say, "Okay, here we have these words. And over here you said this over here. Now we're going to add more description, change the subject, add to the subject, add some adjectives. You put it into lines, make it into stanzas."

But I don't start with stanzas. I start with what's effective and familiar and fun and exciting with the students, at whatever level they are, and with teachers and with people in prison and with people in universities and workshops and wherever I go. So you have to be very flexible.

Physical movement

When you're moving, you go, "Oh, I'm moving. I'm not supposed to do this in the classroom." So you're kind of doing something interesting also.

And you're no longer sitting down. Our writing culture is sitting down with your one arm up or two hands down, and it's 45 degrees pencil or pen or maybe five degrees or 10 degrees off of the keyboard. So that's our writing culture. That never – it never varies.

A painter does this. It's not 45 degrees. A dancer does all the body, right? A clown tumbles, jumps and falls. So since I love art, I said, "Let's borrow from all of them and teach creative writing." So that's what I'm teaching the teachers.

Writing on images

I get very excited as a writer when I write on top of newspapers. I'll write on ads, like on, you know, fragrance ads, perfume ads. I write on Justin Bieber's face, on GQ magazine, because I get very highly stimulated by looking at images, since I've done it since I was a child.

And writing on top of the images – like my father used to write on top of photographs in spelling – "October 24th, 1907. Felipe Emilio Herrera." I have seen that photograph since I was three years old. So now when I look at an image, an ad, I want to write on top of it. It's very stimulating for me. Very inspiring.

Poetry is anti-structure

When you're in an institution teaching, all of a sudden you get institutionalized, but you don't know it. It's very hard, because you have a lot of things you have to do, rules you have to follow, policies you have to follow and standards you have to apply, units you have to teach in particular ways. So all those things kind of crunch you up. And we have to do it. I do it, too. I have things I have to follow. And that's how life is. There's structure and there's also anti-structure, and that's where poetry falls. It's very creative.

Juan Felipe Herrera: Culturally Responsive Instruction

Encouraging Latino students who are from home

When I move around and travel, I meet a lot of students. I meet a lot of Latina and Latino students. And sometimes they're far away from home and the East Coast. And I notice that – I say, "Well, how are you doing in school?" "Oh, doing good." "Well, how come you say, 'Oh, you're 'doing good'?" "Well, because we're far away from home. We are all friends." There's – sometimes there's three or four together. "Well, how do you feel?" "Well, you know, we wish we were back home in LA."

"Well," I said, "I know how that feels a little bit, being far away from home. So what are you going to do?" "I don't know." "Well, it's up to you. But I suggest you stay." "Well, okay." "Because you are pioneers. You are pioneers. And pioneers are the first ones. And they open the road. It's hard. And it's tough. And you don't know what you're doing. But you've got to keep on going."

Mostly what I said, "Thank you for being in this university, far from home, and thank you for being pioneers far from home. You can always go home, too, and visit, by the way, so it's okay too. You’ll be all right." So I meet a lot of Latinas and Latinos in schools and they’re having a hard time. But they are still doing good work.

Giving Latina student indigenous names

So I meet a lot of Latinas and Latinos. They were telling me they like indigenous culture. There were four women, undergrads, first-year undergrads on the East Coast. I said, "Well, you like indigenous – you like Aztec things, huh?" "Oh, yeah. We do danza. So great." "Well, I'm going to give you a name, just for fun, okay?" "Okay." "Well, your name Centeotl from now on. Okay? You're the goddess of corn."

So I gave them four indigenous names. This just happened. And they liked them. "And you're Coatlicue. You're the – you're the actual Earth Mother made out of stone with many powers. Good luck." Then I did two more. And I said – I said, "And you're Haramára, the Huichol goddess of the ocean. Very strong. And you – you're Tatéi Kükurü 'Uimari. You're the goddess of corn too, but you're also part eagle.

So you represent one of the core things about our culture. And corn is very important to the Huichol. So that's what I told her. I said, "You know, that's a very important name, a very sacred name for the Huichol peoples. "Which were the last to be colonized by the Spanish. So I'm just going to offer you that name, and it's for you." "Oh, thank you, thank you, thank you." I said, "Just for fun and for you, those are your names from here on while you're here at the university." So they were very happy to get those names.

Our indigenous culture is very present, but we can't see it because it's not in the media, and it's necessarily – it's not necessarily on display in our cultural – in our teaching institutions, but it's highly available. So I would recommend our indigenous history and indigenous materials. We have a lot of them at the – at the Library of Congress.

Connecting with the experiences of migrant students

The best way to teach migrant education classes and teach migrant education teachers is to be in the migrant experience, which is using words that are familiar. It is using songs that are familiar. Using a personal style that is familiar. Being very, very friendly.

Being very, very tender. Cariño (affection) is a big piece of the puzzle. A lot of acknowledgment. Of course this is true for all classes, but a lot of acknowledgment and a lot of laughing and a lot of enjoyment. If you put those ingredients in, you can teach whatever you want to teach. In terms of – so I would say something: "¿Cómo están todos Uds.? Es un muy bonito día. Me da mucho gusto estar con Uds. I'm so happy to be with you."; (How is everyone? It’s a beautiful day. I’m so happy to be with you)

And it's true. I'm not making that up. "Ahora vamos a aprender cómo hacer guacamole."; (Today we are going to learn how to make guacamole.) And they all laugh. They go, "What? Ah, that's so ridiculous. That's funny. I can't believe it. Guacamole. Yeah."; But I say it because I like guacamole, and I know they've heard of guacamole, and "guacamole"; is never really said in an English-only class. So all of a sudden something that's very silly and very familiar and informal is something very important, is something very meaningful.

There are a lot of materials that our migrant ed teachers can use on the migrant subject. So there's stories. There's poems. There's novels. So it's more easy to do, and more beautiful to do, because then we go from migrant authors writing stories about a migrant experience for migrant teachers for migrant children and communities. So it's a full circle now. And children's books.

How the field of Latino literature has changed

When I first started as a poet in the – in 1966, we didn't have any materials of Latina, Latino poets, and if we did they were impossible to find. They were nowhere to be found and nowhere to be taught. So by 1971, when one of my friends, Alurista, published his book, Floricanto, at UCLA Chicano Research Center, that was the first poetry book as a book written by a Chicano that we had in our hands. There was – there were anthologies before that. El Espejo had Jose Montoya's poetry in it.

From Berkeley. But as a book, it was really exciting. It was bilingual, like Espejo was. This was fabulous. However, this is 2016. We have hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of poetry books and hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of hundreds of Latina and Latino novels and a lot of art and photography and dance and theater.

I encourage teachers to use as many cultural assets, cultural experiences, cultural materials, cultural community most of all – most of all – and bring it all into the classroom in as many ways as possible.

Thirty kinds of "mole";

I met a student in Turlock, California, just last month. I went to read at the Carnegie Art Center, Cultural Center there in Turlock, California. It's close to Sacramento.

And I was talking with one of the students from Hidalgo, Mexico, on the perimeter of Mexico City or close to that area. And for some reason, I mentioned mole, because I like to play with words nonstop. And – "Mole?" I said, "Yeah." "Oh, you know, where I come from, there's like 20, 30 kinds of mole." I go, "What? Twenty, 30 kinds of mole?

"I know about mole colorado, mole negro, and that's it. And you?" "Mole de galleta." "What? Crackers? Mole made out of crackers?" Well, I'd have to tell you later, but there's many kinds of mole in Hidalgo. So you see, if one of your students is from Hidalgo, they're going to know about mole. What is mole? Well, it's kind of like a really cool thing to cook and make and use it for celebrations.

But what does that all mean, anyway? Well, there's stories behind the mole. They come from Oaxaca. They come from Hidalgo. And what do you learn from that? You learn kind of a – you learn about food. You learn about family. You learn about special cultural occasions where you use the mole. Who cooks it? How do you learn to make it, and where do you get the materials? Where do you –

What kind of chocolate is it in Oaxaca, and why red and why black? When do you use the red kind? All of a sudden, you have – the culture opens up out of what – out of one little tiny thing. What is it called? It's called mole. Or a molcajete. And you examine the molcajete, start talking about it with a family that uses it, you're going to get the whole family and you're going to get the whole community.

And then all of a sudden, the whole culture starts appearing out of one little thing. Or how to make masks from Michoacán. Michoacán mask makers. There's probably one in your community. Bring them to – bring them to the class. So how do – contact and getting contact with direct and real cultural experience and materials and elements that you – that you can use in your classroom – you have it right in front of you.

So explore that. And you can also explore the local cultural organizations on – in your community. Michoacán has very strong organizations. Oaxaca has very strong cultural organizations in the city, in particular cities, not all of them. Some communities are very highly organized culturally. So I would go to them for sure.

"How many of you have heard that story?" Teaching folklore through students' cultural experiences

Our community is a university, a cultural university, our community. The school itself is also a school, and the teacher of course is a teacher. But believe it or not, the students themselves and their families and their community is where it's all available. All the cultural material is available, and it changes every day, and some of it is there generation after generation. So that's where we need to go.

And I'll give you an example. I was teaching a Chicano folklore class at Cal State, Fresno, in the Central Valley of California. And I was teaching a folklore class. And I told myself, "I'm going to turn it around. I'll turn it upside down."; I said, "Students, we're going to – we're not – I'm not going to teach anything here. I'm not going to present any material. You're going to present the material. And you're not going to get it from me or from the books.

"As a matter of fact, you're going to get it from your house and from your parents, aunt and uncles, and from your community at large. But before we do that, I want you to say out loud kinds of stories that you have heard. What are some stories that you have heard?"; "Well, about crossing the border."; So I put stories about crossing the border.

"And what other kinds of stories or legends have you grown up with?"; "Oh, La llorona."; "And what else?" "Oh, about the ghost in Avocado Lake over here by, at the edge of Parlier, next to Fresno." "Okay, the ghost of – the ghost in Avocado Lake. And what other kind of ghosts have – are you familiar with?" "Oh, oh, you know, the lost treasure of Pancho Villa."

"How many have been – heard about the lost treasure of Pancho Villa?" A lot of hands went up. So I put that up. Because I'm after the stories of the people. Folklore. The stories of the people. Which is a major piece when we think of cultural assets – folklore, stories, legends, sayings, invented stories or word games. Verbal art. All that is part of folklore, which is part of culture. Not ideas of culture, but the actual material culture, which are the stories in this case.

"And what else do you have?" "Oh, the story of Moctezuma's hidden treasure." "Okay. How many have heard of this, of Moctezuma's treasure?" "Oh, yeah, you know, he just – he left a lot of treasure buried somewhere in Mexico by the pyramids." "How many have heard of something like that?" A lot of hands went up.

"How about Pancho Villa?" "Yeah, my grandmother knew Pancho Villa. My grand-grandmother" – "How many of you family – had family members that knew Pancho Villa?" A lot of hands go up. So then we need those stories. So then after it was all said and done, I had around 400 pages typed of folklore from those students' communities in the Central Valley of California.

So this is a big project. It was called La Mano Peluda, "the hairy hand," because it told a lot of scary stories. This is a particular kind of project. This example that I'm saying is that you can collect stories that the students already know and the parents may already know and the grandparents and their community knows, but first you have to bring it out and then put it on the board. Or screen. Or provide an example. And then you'll see the hands go up.

Parents become the teachers

I had a group of people, of parents, in Oregon. I was in – close to Portland, Oregon. It was a community where parents worked in the nurseries. They're called – they're called las nurserías. They worked in las nurserías.

And I was teaching this very same book, Calling the Doves, and they were in a circle in front of me, around six of them, not that many. Not that many. And again, I didn't want to come in and talk as a professor or as an author. That's not going to work. I'm going to come in and talk as a family member, as close as I can, as a friend, and give them a book and then do that quickly.

And when I say, "What's – you know, this is what I did, but I'm more interested in what you do, so if you want to recite, sing a song, let's do that, okay? And if you want to just say a dicho, let's do that." And I said all this in Spanish, because I know – I know that dichos and riddles like I grew up – and songs – are still very important.

And they know many. Many. So we went along and – until we got to one man who had been really out in the sun. He was very dark brown. And he was dark brown. And I know he was a hard, hard, hard campesino worker, like all of them were, and their children were in the school, and I was a visiting author. Okay.

So when it got to him, he shared a song. And it was a real song. And they all heard him, and it was very meaningful. It was very meaningful. It was a song. It was a song they knew. It was a – it was a cultural thing, for sure. For sure. But it was like a lightning bolt, because he sang it with every part of his heart, and they felt it. They felt it.

It was a song from where they were from, and it was never sung. And he sang it. So it was beautiful. It was beautiful. So when we do this with our community, they become the teachers, and we – the teacher – you know, the teacher in the classroom, you know, you can pick, you can choose and use those materials after they leave class.

You know, you can talk about corridos. You can continue it. But for the parents to be in the classroom is great for the students. They're going – they're going to bring something real, something new. It's great for the students. Great for the teachers. It's going to add to the teachers' materials. And you're going to let the students know that, "Your culture is valuable, because it – this came from you, from your parents, by the way. Because you – did you ever think your parents would be teachers?"; "No."; But they are. So it helps us in many ways. And I like to do that.

I would bring parents as speakers. I would have the parents create a workshop. I would have – whatever works that they want to create, you know, invite your community. Invite the parents. And I know not all parents are available. They're working hard around the clock, and they – invite them to school. One way or another. Slowly but surely bring them to your classroom.

Juan Felipe Herrera Reads His Poetry

Juan Felipe Herrera reads from "Calling the Doves"

My name is Juan Felipe Herrera, and I'll be reading from my book, my first children's book, which is Calling the Doves: El canto de las palomas. And I want to read you a particular section about the road, okay?

"The road changed with the seasons. In the winter in Delano, my parents trimmed grapevines. By springtime, we headed to Salinas for the picking of melon, lettuce and broccoli. When summer began, we drove back to Delano and Parlier to prune the grapes so that a few would grow the sweetest. By the end of summer, as the leaves turned colors, we'd travel through the valley picking the grapes. We'd lay them down, out on the ground to dry, on long sheets of paper between the vines. In time, with the sun, the tiny, fiery planets would stop glowing and shrink into dark raisins."

Excerpto: "El canto de las palomas"

Yo soy Juan Felipe Herrera, y les quiero leer de mi primer libro para niños y niñas, que se llama "El canto de las palomas", y les voy a leer una sección que está en medio del libro que habla del camino de los campesinos, nuestro camino, de mi familia campesina.

"El camino cambiaba con las estaciones.

Durante el invierno,

mis padres podaban vides en Delano.

En la primavera nos íbamos a Salinas

para la pisca de melón, lechuga y bróculi.

Al comienzo del verano,

regresábamos a Delano y Parlier

para recortar racimos de uvas para que

algunas crecieran más dulces

Ya para el fin del verano,

cuando las hojas tornaban de color,

cruzábamos el valle piscando uvas.

Para que se secaran, las extendíamos

en tiras de papel sobre la tierra.

Y con el tiempo, en el sol, los pequeños y

luminosos planetas terminaban de alumbrar

y se volvían oscuras pasas.

Imagine

If I picked chamomile flowers as a child in the windy fields and whispered to their fuzzy faces –

" – if I let tadpoles swim across my hands in the wavy creek, if I jumped up high into my papa's army truck and left our village of farm workers and waved adios to my amiguitos, if I let the stars at night paint my blanket with milky light, with shapes of hungry birds while I slept outside, if I helped mama feed the hopping chickens and catch the crazy turkey in the front yard of our new village –

" – if I left and walked through the evening forest at the top of the mountain with a silvery bucket to fetch water from the next town, if I moved to the winding city of tall bending buildings and skipped to a new concrete school I had never seen, if I opened my classroom wooden door not knowing how to read or speak in English, if I practiced spelling words in English by saying them in Spanish, like, 'pen-seel,' for 'pencil' –

" – if I collected gooey and sticky ink pens because I loved how the ink flowed like tiny rivers across soft paper, if I grabbed a handful of words I had never heard or sprinkled them over a paragraph so I could write a magnificent story, if I stood up in a school far away from where I lived and sang for the first time in front of class, if I started to write a poem on a skinny paper pad after school as I walked on the white sidewalk and then finished it when I got home –

" – if I picked up my honey-colored guitar and called out my poem day after day and turned it into a song, if I gathered many words and many more songs with both of my hands and let them fly over my mesa and turned them into a book of poems, if I stood up here in front of my familia and all of you on the high steps of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and read out loud like this –

" – imagine what you could do." So that's what I read at the inaugural opening session, first time I was the Poet Laureate of the United States.

I forgot about this. Yeah, it's going to come out.

(Applause)

Did you like that one?

Off-camera: That’s what Poet Laureates do.

What it all about?

How do we deal with the problems in our communities? How do we deal with the problems in our nation? Or how do we inspire others? It has to begin with you. It has to begin with you. And it begins with you, every part of you, every word of you, every dream and imagination, thought that you have.

And we have – you have to channel it out. You have to slap it on paper. You have to speak it out. And I'm here to help you. It's very easy. I'm just – I'm here to help you. And I'm here to remind you. And I'm here to invite you.

Is it important? It's up to you. I think it is. Are you going to be able to contribute something? Are you ready? I think you are. And I think you will. Will it take a long time? I'm here to say you can do it right now. Do I care about poetry? I do. Should you care about poetry? It's up to you. What, really, is it? It's your entire life. What does that mean? That means giving. It means opening. It means accepting. It means including. It means creating.

Well, what do you have to create with? Everything. When do I do it? All the time. How do I do it? Any way you want. Do you have to know something ahead of time? No. Why? Because it's all you. That's why. Well, what do I have to give? Your voice. And what is your voice made out of? Everything.

Ideas, memories, experiences, imagination, words, images, dreams, instantaneous thoughts, ideas that happen right now when you see something, an issue, a human being, an animal, the community. When you hear something. You remember. A photograph. Respond. What does a response do? It supports us.

If we walk alone and never respond, you will go – you will get lost. We will not know who you are. We will not know about your family. We will not be inspired about our family. We will begin to walk alone too. You will inspire us to walk alone. And when you respond, you inspire us – you inspire us to respond, and when we all respond, we can all hold each other together. When times are hard, they won't be so hard. When we don't know what to do, we will begin to know what to do.

But step number one is you. Step number two is responding. And step number three is enjoying it all, because that's what life is all about. That's what I do.