Several years ago, I met a high school math teacher named Hillary Hansen who had just taught her first Basic Math course for English language learners (ELLs). She wanted so much to provide the students with the good foundation they needed, but she felt unable to engage them in her lessons. By the end of the year, she was exhausted and frustrated.

That summer she had an opportunity to join a district Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP) cohort to receive professional development and support the needs of ELLs in content classes. She learned about the importance of language acquisition, building background knowledge, increasing student language production, and explicitly teaching academic language. She began the following school year with a new set of tools and a deeper understanding of the instructional scaffolding ELLs need in order to learn the content while also learning English.

While Hillary still felt challenged and was working hard, the second year was much more successful for her and her students. She felt she was providing them with the foundation they needed not only to understand the mathematical concepts, but also to successfully interact within a math classroom in order to learn more advanced concepts.

As a result of more effective instruction, her students:

- Understood the content better and were working together to find creative ways to learn

- Increased their participation in discussions and learned how to use instructional supports in the class

- Felt more comfortable with math and asking questions to get the help they needed

You can learn more about some strategies that Hillary and other teachers recommend for teaching ELLs math in the information below, along with reflection tips and ideas for getting to know your students' math backgrounds.

ELL Math Resource Collection

This resource collection features several ideas for teaching math to ELLs.

Reflection Questions

- How much math instruction have your ELLs received in their prior schooling?

- How much do their levels of math background vary?

- What are some of their strengths related to math?

- What are some of their challenges?

- What are some practical ways your ELLs are using math in their daily lives?

- What kinds of strategies have supported their success or engagement in other areas?

- What are some ways that collaboration or co-teaching might support your ELLs?

- What are some leadership opportunities you might give ELLs in pair work or small group work?

Learn About Students' Math Backgrounds

Teaching ELLs: Tips for Math Teachers

It's important to remember that ELLs' math backgrounds may vary significantly. Some students may have had consistent schooling where they developed strong math skills. Others may have limited or no formal schooling, but may have practical skills related to time, money, or other daily topics. If possible, find out whether students have attended school regularly and what kind of experience they have had with math instruction and with math in general. Look for ways to tie instruction to student interests (like sports) and responsibilities at home that involve math, such as helping with family finances, working in family businesses, and holding other jobs. For example, students from migrant farmworker families may be using math related to agriculture, such as weighing or selling produce. Also keep in mind that students may use other numeric and measurement systems students, such as metric system, Celsius, military time, etc.

In addition, Pennsylvania educators Sally Lopez and Erin Minick also encourage educators to:

- Look for leadership opportunities for all students in math class

- Provide students with opportunities to "teach" others, work together, and demonstrate what they know in multiple ways

- Group students intentionally and with sensitivity, avoiding the designation of specific students as "needing more help" in their grouping, partner assignments, or placement in the classroom

(Ms. Lopez and Ms. Minick conducted a book study focused on Teaching Math to Multilingual Students, which you can learn more about from their website.)

Keep in mind that veteran educators of ELLs also stress the importance of getting to know students as a key part of supporting student success. For example, in this NCELA webinar, Dr. Haiwen Chu, a national expert on mathematics education for English Learners at WestEd, recalls that visiting his high school students' neighborhoods provided valuable insights on their experiences and familiar topics.

See additional ideas for getting to you know your ELLs in 10 Strategies for Building Relationships with ELLs.

The Language of Math

Although it is easy to assume that many ELLs will excel in math class because math is a "universal language" and students may have had prior educational experience that included mathematical instruction, that assumption can lead educators astray. While computational skills may transfer, ELLs may still need support with language-focused tasks, such as solving word problems, learning (and using) math vocabulary, and writing explanations. All of these skills require a language proficiency that sometimes exceeds our expectations. We tend to think of mathematics as a subject that does not require a strong command of language. In reality, however, mathematical reasoning and problem solving are closely linked to language and rely upon a firm understanding of basic math vocabulary (Dale & Cuevas, 1992; Jarret, 1999), especially when considered along with the demands of college- and career-ready standards.

Co-Teaching and Collaboration

For many educators, the challenge of bringing language and math instruction together is a relatively new one. ELL teachers who hadn't taught content areas previously are now being asked to lead or support instruction in the math classroom, and many math teachers who don't see themselves as language instructors are now responsible for providing effective math instruction to ELLs. When educators collaborate, however, they can better understand each other's expertise and combine their expertise for the benefit of students.

For example, when planning a lesson, a math teacher and an ELL teacher could collaborate to identify both the target content, such as key standards, concepts, or specific topics, as well as key vocabulary, academic language, and the language-focused tasks students will need to complete the lesson. These tasks might include writing out a proof, reading a math problem, explaining how to solve a problem, or writing out numbers as words. The ELL specialist could walk the math teacher through this process several times so that it becomes a more integrated part of the math teacher's planning over time. After the lesson, the teachers could identify other areas of focus or clarification needed and share these insights with their colleagues.

Another tool content teachers can use is language objectives, which help target the language demands of the lesson. You can learn more about them in the videos featuring Mr. Jesus Ortiz below.

Teaching Academic Vocabulary

Vocabulary instruction is essential for effective math instruction. Not only does it include teaching math-specific terms such as "percent" or "decimal," but it also includes understanding the difference between the mathematical definition of a word and other definitions of that word, as well as understanding the concept a vocabulary word describes.

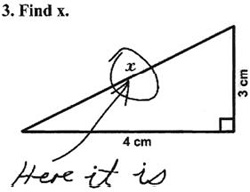

The following example, used in a presentation by Dr. Judit Moschkovich of the University of California at Santa Cruz, underscores why vocabulary must be introduced within the context of the content (Moschkovich, 2008):

In this problem, the student is instructed to "find x." The student obviously knew the meaning of the word "find" because they "found" it on the page and circled it. The student even put a note on the page to help the teacher in locating the lost "x". The student understood the meaning of "find" in one context, but not in the appropriate mathematical context.

I recently helped a math teacher create a sheltered lesson, and I was surprised to find that there were some vocabulary words that I didn't understand. My lack of familiarity with the words hindered my ability to do the math problem and gave me a deeper empathy for ELLs who struggle in the same way with vocabulary and comprehending math assignments.

Following is a list of tips for explicitly teaching mathematical academic vocabulary.

Teach key academic vocabulary

After you identify your target content, identify the academic vocabulary words that students will need to understand that content. Some of these key phrases or new vocabulary words may also be helpful to pre-teach in small groups or mini lessons. Think about:

- Academic vocabulary (equilateral)

- Words and phrases needed to solve a problem (less than, given, arrange)

- Common words needed to solve word problems (train station, dolphin, favorite)

- Homophones (eight/ate, plane/plain, one/won, two/to/too, four/for, some/sum)

- Words that students are likely to encounter in other settings (formula, prove)

- Words that represent a numerical value necessary for solving the problem, such as measurement words (foot, feet, meter, pounds, kilometers)

After you identify the vocabulary you wish to teach, use scaffolds for academic vocabulary, such as:

- Visuals: These can include visual representations of concepts, photos, and illustrations of key vocabulary words, posters, and number lines.

- Realia (real objects) and manipulatives: These might include hands-on objects related to a topic or small items, such as coins or small blocks for counting, sorting, weighing, etc.

- Graphic organizers: Graphic organizers are tools that allow students to organize information in a visual or hands-on way.

- Anchor charts: Anchor charts are posters that students and teachers co-create to highlight key concepts and vocabulary that students will need for reference.

Offer students the chance to work with objects and images in order to master vocabulary. If there aren't enough items for each student, use manipulatives on the overhead or posted throughout the classroom, and demonstrate the vocabulary in front of the students. For example, Hillary created a Math Word Wall that has three parts: key vocabulary, "in your own words" definitions, and a variety of ways to portray a function. For example, multiplication is portrayed by the following symbols: x, *, and ( ).

In addition, it can be helpful to ask students which strategies support their learning. Students often can provide valuable information on what is working for them!

For examples of how vocabulary can impact students' understanding of math problems, see the related video with ESL teacher Anne Formato below.

Teach words with multiple meanings

Demonstrate that vocabulary can have multiple meanings. Help students understand the different meanings of words, as well as how to use them correctly in a mathematical context. This is also a good opportunity for using visuals and realia. Examples include:

|

|

|

Draw on students' home languages

- Use cognates, which are related words in two languages. English and Spanish have many cognates within academic terms, like fraction/fracción.

- Use translated words or phrases strategically. For example, New York University has published bilingual glossaries for several topics.

- Allow (and encourage!) students to use their languages in group work to solve problems, brainstorm, and review material. Students will understand material better if they explain it to another student, and the new student will benefit from hearing the explanation in their first language.

Increasing Student Language Production

The language demands of math are complex. Working with an ELL specialist can be a good starting point for identifying some of the math demands of the lessons you are teaching, as well as for planning how to teach and scaffold those language demands.

As I've worked with content area teachers in my district to develop Sheltered Instruction lessons and activities to enhance ELL learning, I've told them, "If a student doesn't say it in your class, they're never going to say it." This is a bit dramatic, but it's true to some extent. When students learn new vocabulary, the opportunity to use it must be presented in class, because students are unlikely to try it out on their own — especially academic words like "parallelogram" or "function"!

Here are some tips to increase student-to-student interaction with academic language in the math classroom:

- Have students translate symbols into words, and write the sentence out. Hillary used this strategy to check students' comprehension of problems before they solved them. For example, 3x + 4 = 16 would be written out, "Three times X plus four equals sixteen." This helps students process the operations involved in the question and gives them an opportunity to think through how to solve it. It also gives students a chance to familiarize themselves with important vocabulary words. Writing out the answer to a problem is a very important skill to develop because many state math tests require a constructed response to questions.

- Create a "sentence frame" and post it on the board. Write the format of the sentence you would like students to use in discussion and then hold them accountable for using it. For example, "The answer is _______ degrees because it is a _________ triangle. (Learn more in our sentence frame and sentence stems strategy.)

- Have students share problem-solving strategies. This involves asking a simple question, such as, "Did anyone else get the answer in a different way?" Then allow enough wait time so students can think through how their problem-solving process was similar or different to the one offered.

- Allow students to discuss how they are thinking about math. This is a way of redirecting the lesson from teacher-to-student to student-to-student. For example a student might ask a question, "How do you know what kind of triangle it is?" Instead of the teacher answering and going to the board and pointing out the names and different triangles, the teacher can simply ask, "Does someone have an answer? Or "Would someone like to offer help to Mario?" Allow students to share how they think about the math concept and any tips they have for remembering the information.

- Incorporate writing activities, such as entrance/exit tickets or math journals. This is an excellent way for students to process what they've learned and what questions they still have. The journal or exit/entrance ticket prompt could start with simple prompts such as, "One thing I learned today..." "One thing I still don't understand…" "One way I can get the help I need…" "The answer to this problem is…" "Something that helped me was..."

- Challenge students to create their own math problems. This can be a fun activity if students create a problem similar to the ones you have used in class and they exchange problems with a partner. By creating the problem and checking the answer they are reinforcing their own learning.

- Teach students how to read, interpret, and summarize data. Provide students with explicit, step-by-step instructions in how to read charts, graphs, tables, and infographics, as well as how to describe what they observe in visual representations of data.

- Model the kinds of writing students are expected to complete (e.g., written explanations). Students need to see and understand what they are expected to do and produce, such as explaining how they solved a math problem. This is a great opportunity for the "gradual release" strategy -- I do, we do, you do.

- Try AI tools. Consider using AI tools to rewrite math problems for students at early levels of proficiency or to generate math problems with familiar vocabulary that achieve your target objective.

Reading and Understanding Written Math Problems

Written word problems present a unique challenge to ELL students and teachers alike. In Reading and Understanding Written Math Problems, Brenda Krick-Morales writes, "Word problems in mathematics often pose a challenge because they require that students read and comprehend the text of the problem, identify the question that needs to be answered, and finally create and solve a numerical equation — ELLs who have had formal education in their home countries generally do not have mathematical difficulties; hence, their struggles begin when they encounter word problems in a second language that they have not yet mastered" (Bernardo, 2005).

Teacher Xiao-lin Yin-Croft has encountered this pattern in her classroom of bilingual Chinese students in San Francisco. She has developed a very creative way to use her students' background knowledge of math as a stepping stone for other language learning. She does this by accelerating math instruction at the beginning of the school year and then building on what students have learned in math in reading and other content areas. In Building Bridges for the Future, Xiao-lin explains her strategy:

First, we read math word problems; I demonstrate the logical thinking process while translating words into pictures and, finally, into number sentences. Soon, they start to explain their own thinking after reading complicated word problems that involve several steps. They correct each other and argue about which number sentences they should use to arrive at the correct final results. As they sharpen their math skills, I capitalize on their enthusiasm to teach them how to extract the most important information from texts, and move them toward the oral and reading fluency they need to understand and discuss more challenging texts.

Even if you aren't accelerating math instruction, however, there are a number of ways to help students master word problems. Krick-Morales offers suggestions in the previously mentioned article, such as explicit instruction of key vocabulary, daily practice of problem solving, repeated readings of the word problem together as a class, and hands-on activities such as movement, experiments, or drawing to help students comprehend the problem. As students become more familiar with math vocabulary, they will be able to solve problems more easily.

Identify key background knowledge in math problems

It's important to identify what kinds of background knowledge students will need to understand a math problem. For example, Ms. Lopez and Ms. Minick used this activity with a conference session: Ms. Lopez chose four math problems from her son's math textbook and asked session attendees to brainstorm the kinds of background knowledge students might have questions about, some of which were relevant to solving the problem and some of which weren't. Here are some things that attendees came up with:

- A math problem about a coupon and sales tax at a dog groomer: What is a dog groomer? Why do people take their dogs to get groomed? What is sales tax? What is a coupon? What is "deluxe"? What is an estimate and a discount?

- A math problem about people receiving a voucher for a free water bottle at a football game: Is football different from soccer? What is a voucher? Does the water bottle come with water inside it?

- A math problem about a fishing pole on sale: What is "percent off"? What is a sale? What is "regularly priced"? What steps have to be followed to solve this problem?

- A math problem about calculating a tip in a restaurant: What does "leave a tip" mean? What is a tip? Does the fact that there are four sisters (Emilia and three sisters) impact the outcome of the problem? Why aren't they using an app like Venmo?

As seen from the example above, this can be a powerful area in which math teachers and ELL teachers can collaborate.

The Role of Background Knowledge

When it comes to background knowledge that impacts students' understanding of new concepts, students may have relevant experiences to what you are teaching that just need to be drawn out (as in the vignette below). In other cases, students may not have the needed background knowledge. My colleague Hillary found that sometimes her students would get "lost" in a problem simply because they didn't understand the context. Following are some tips to help in tapping into and building background knowledge of students.

- Identify connections to your students' experiences. When planning the lesson, consider whether they might have relevant experiences, and as you introduce the lesson, find out what they know, giving them an opportunity to make connections. They may come up with connections you never had imagined!

- Modify the linguistic complexity of language and rephrase math problems. Students will understand the problem better if it is stated in shorter sentences and in language they understand. This may be an area in which you wish to experiment with AI tools that can rewrite problems.

- Guide students to cross out the unnecessary vocabulary in word problems. Doing so allows students to focus on the math function required. For example, one problem Hillary's students came across referred to a "school assembly." Even though the meaning of that phrase wasn't important in the solving of the math problem, students didn't know it wasn't important, and the lack of understanding contributed to their confusion.

- Build knowledge from real world examples. Try to reinforce concepts with examples that students can picture and talk students through the situation. For example, if you need to paint a room, you need to know how much area will be covered so that you know how much paint to buy. Look for familiar ideas or props that can be used to engage students such as recipes, news stories about the economy, or discussion of personal spending habits.

- Use manipulatives purposefully. This is important at all grade levels. Hillary has found math cubes to be very useful in having students represent the numbers in the problems and then manipulate the cubes to get the answer. She used the cubes and the terms "hot" and "cold" numbers when teaching with the concept of negative numbers. Students would use the red cubes as "hot" or positive numbers and the blue cubes as "cold" or negative numbers. As students laid out the number of hot cubes and cold cubes represented, they could easily see if the answer would be a positive or negative number by which color had the most cubes. A problem such as -2 + 1 = -1 would look like this:The student then removed pairs of cubes — one red, one blue — until they could no longer remove any blocks. The remaining blocks represent the answer.

Using Technology

Technology can also be a powerful tool in math instruction for ELLs. Here are some ways you can play with technology in a math lesson:

- Look for educational resources that accompany your school's technology tools and programs. There may be online or software programs available for teachers. For teachers who have an electronic whiteboard in the classroom, there are many resources available on links that can be easily accessed and brought into the classroom.

- Find out what's available online. Both PBS Learning Media and Vital NY (Video Teaching and Learning for NYS Educators) on Teachers' Domain offers an online library of free public media resources. Teachers' Domain resources include video and audio segments, Flash interactives, images, documents, lesson plans for teachers, and student-oriented activities. (Free registration required.)

- If students are using a calculator or other device, ensure that they learn how to use it. Based on background and prior educational experience, students might not be familiar with how to use a calculator, graphing calculator, or math apps on devices such as phones or tablets. Give students a chance to practice solving problems with their calculators once you have reviewed different functions. Texas Instruments offers numerous activities and product tutorials in their educational materials.

- Learn more about how to use AI tools in math. AI tools can be used to generate, differentiate, or rewrite a math problem; create a summary of a lesson plan; and many other tasks. Keep in mind that AI-generated content always need a careful review and edit. (See more in Using AI in Math from Edutopia.)

- Look for interactive games that offer students a chance to practice their mathematical skills. Nintendo DS has an educational game called Brain Age, which is not language specific. The game provides excellent mathematical training for numbers and tracks results, showing student improvement over time.

Books About Math and Mathematicians

In addition, there are lots of books about math and mathematicians that you can incorporate into your classroom and classroom library. You can see a wide range of titles for different ages in our Math Resource Collection.

Closing Thoughts

Even if it doesn't come easily at first, there are ways to get ELLs excited about math. By keeping their language skills and needs in mind when planning mathematical instruction (and by helping your colleagues do the same), you will be taking important steps in helping students master mathematical concepts and skills. You never know — your students may be the next generation of economists, rocket scientists, and math teachers just waiting for the tools they need!

Note: I'd like to thank my Minnesota colleagues, Hillary Hansen at Burnsville Senior High School and Kim Olson at Hidden Valley Elementary, as well as Xiao-lin Yin-Croft from San Francisco, for providing many of the helpful math teaching tips in this article. It is inspiring to know that there are talented, creative teachers who are always finding better ways to teach and are willing to share the knowledge.

Related Videos

How vocabulary can get in the way of solving a word problem

ELL Specialist Anne Formato talks about the trouble a student had in understanding a written math problem based on a vocabulary word.

Teacher Alejandra Rojas: Why cognates are your "best friend" in math class

Elementary teacher Alejandra Rojas, who teaches in a dual-immersion program, explains why cognates support vocabulary development in her Spanish-language math class.

Teacher Alejandra Rojas: When bilingual students translate for their parents

Alejandra Rojas, a teacher at a dual-immersion school in Arlington, VA, shares some of her experiences as a child and teenager translating for her mother.

How to Write Language Objectives: Tips for ELL Educators

In this video from Syracuse, NY, Jesus Ortiz, a bilingual teacher, learns how to write a language objective from Areli Schermerhorn, a peer evaluator with expertise in ELL and bilingual education.

Teacher Observation Cycle: A Math Lesson on Pictographs

This video highlights Mr. Ortiz's math lesson on pictographs. While the main topic of the video is teacher evaluation, numerous best practices and strategies related to math instruction for ELLs are mentioned in the video.

Recommended Resources

- NCELA Teaching Practice Brief: Math (A related podcast is available as well)

- Supporting English Learners in Math and Science: Effective Instructional Practices and Examples from NCELA’s Teaching Briefs

- PBS Learning Media: Math Lessons

- EngageNY: Common Core and Math

- Common Core Math and ELLs: Blog Posts

- Discovery Education: Puzzlemaker

- Catherine Snow: Word Generation

- SMART Notebook Lesson Activities

- Translating Word Problems

- Colorín Colorado Webcast: English Language Learners in Middle and High School

Comments

Deborah Ortiz replied on Permalink

Wow! This is an awesome site with many practical instructional ideas to help our English Language Learners. Thanks!

Carlos Malcon replied on Permalink

Awesome!!! There is no doubts that there are a lot of researches behind these great advices and point of view of teaching math. I am a Honduran teacher conducting an Extensive Reading program. Thank you!!!

Maestra en Mexico replied on Permalink

Thanks so much for sharing your knowledge. This is one of the best articles I've read with ideas for teaching math to ELLs. We'll be putting these ideas into practice in our bilingual school in Mexico.

Mercy replied on Permalink

Thanks a lot for this words on how to tackle question in reading math. I have similar problem understanding principle of math 12! I feel like drop out of the course but now , this words of advise which i refer to as "“teaching knowledge †has fully encourage me to continue and complete my course. I hope to do better from reading this words and encourage the writer to keep doing a very good job .

Linda Witas replied on Permalink

good information

Natalia Ferrell replied on Permalink

Thanks a lot !

WONDERFUL !

llooll replied on Permalink

Thank you very much, this information and advices were really good, Now i can Sleep better!

Sukaina replied on Permalink

Thanks for sharing, its really informative and intersting

Tarry replied on Permalink

Thankyou for sharing. I am working on a reserach paper and your post has given me a good structure for helping me crystallise my ideas.

Jane M replied on Permalink

Wow, thank you so much for this article! I'm doing my teaching practicum in a school with a large percentage of ESOL students at all levels and this is extremely helpful... I'm going to put these suggestions to use immediately!

khosraw replied on Permalink

good work

Ruchira Modi replied on Permalink

Thanks! We are building math animations for ELLs and your article was very helpful.

Shaunagh Smith replied on Permalink

This is extremely beneficial. Thank you. When was this article published?

Kate Reidy replied on Permalink

I love the ideas of writing the math sentence with math symbols into words. Another effective practice is allowing students to offer their way of determining the answer-it creates community as well.

Almondo Smith replied on Permalink

I liked how the article talked about math being a universal language witch helps with their vocabulary

Joan Tana-Guercio replied on Permalink

Thank you. I'm using your website for my CTEL course. It's very helpful and informative. I'm a high school math teacher in the US and English is my second language.

Add new comment