Educators must comply with federal laws, policies, and regulations governing the education of public and public charter school education of multilingual learners (MLs). This article provides an overview of the federal laws, regulations, and court cases governing language assistance programming.

A Note on Terminology

The strengths-based term multilingual learner is used throughout this document to recognize and value students' existing language abilities and highlight what they know. Keep in mind that states may use different terms and that many federal documents use the terms "English learner" and "Limited English Proficient students."

See the federal definition of a multilingual learner in Who Are Multilingual Learners?

Guiding Questions

Download this guide

This guide is also available in a PDF version for download and printing.

This guide is also available in a PDF version for download and printing.

- What are the landmark court cases regarding language assistance programming for MLs?

- What are the key federal education acts governing the education of MLs?

- What action steps should be taken to analyze the effectiveness of the language assistance program in my school?

- What is the Dear Colleague letter and how does it provide guidance on the eudcation of MLs?

Federal Education Acts Governing the Education of MLs

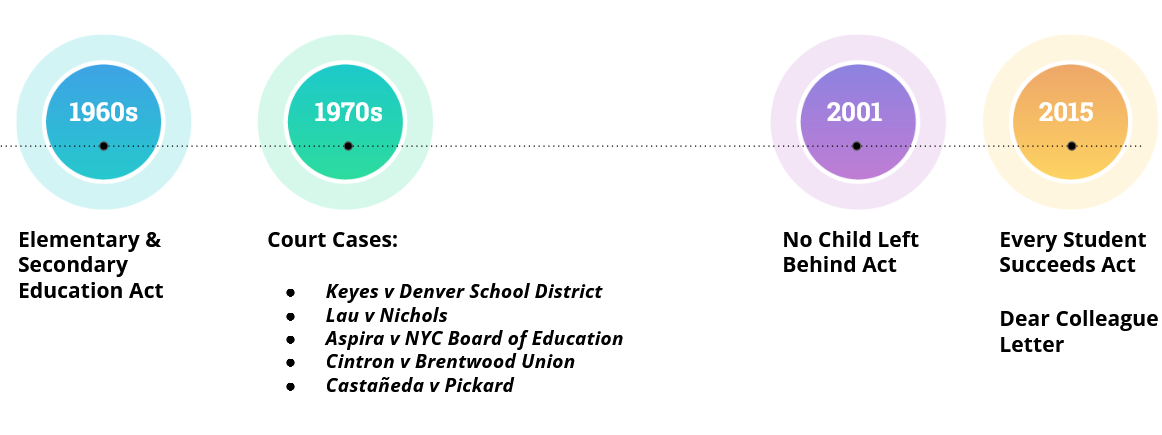

The federal education regulations governing the education of all public and public charter school MLs are an outcome of major historical events. Many of the laws result from federal acts and significant court cases. Illustrated in Figure 1.1, each is intended to provide safeguards for MLs to receive a quality education, learn English and content successfully, and remedy obstacles and barriers to learning.

Figure 1.1: Federal Acts and Court Cases Related to Multilingual Learners

Key Education Laws

In the United States, federal education laws prohibit discrimination and ensure equal access to an education. The laws and regulations regarding the education rights of MLs are the result of federal actions intended to equalize students' access to education and include the following:

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act was enacted. It ruled that any institution receiving federal funding cannot deny access to anyone from any program or activity based on their race, color, and national origin (U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Civil Rights, n.d.).

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act [ESEA] of 1965 was amended in 1968 and was the first federal education statute to bring the rights of MLs into focus. The purpose of the amendment, known as the Bilingual Education Act, was to support MLs in attaining proficiency in English and meeting educational standards.

The No Child Left Behind Act [NCLB] of 2001 was enacted to improve student achievement and ensure that all students received a high-quality education and met state academic standards. The standards included four major principles:

- Stronger accountability for results;

- Greater flexibility among the nation's states, school districts, and schools in the usage of federal funds;

- More choices for parents of disadvantaged backgrounds; and

- An emphasis on teaching methods that are proven to work (U.S. Department of Education, 2002).

ESEA was amended in 2015 under a new name, Every Student Succeeds Act [ESSA]. It reinforced our nation's promise to provide students with equal opportunities to an education and established standards to ensure the success of all students (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). ESSA requires every state education agency [SEA] to "monitor every local education agency [LEA] to ensure that they are providing ELs with meaningful access to grade-level core content instruction and remedying any academic deficit in a timely manner" (U.S. Department of Education, 2016, p. 1).

There are many activities that schools and districts must follow under the ESSA. These include:

- Monitoring MLs' progress in becoming proficient in English and learning core content;

- Establishing benchmarks for expected growth and steps for supporting students who are not making progress toward these goals;

- Using valid and reliable assessments in the areas of listening, speaking, reading, and writing and documenting the progress of MLs in learning English;

- Monitoring former MLs for at least two years to ensure they were not exited prematurely, any academic deficits are addressed, and they are successfully participating in the standard program alongside their never-ML peers; and

- Reporting the number and percentage of former MLs who have met state academic standards for four years (U.S. Department of Education, 2016, pp. 1-2).

In addition to the rulings of federal courts, described in the succeeding paragraphs, federal policies about MLs follow various federal acts, including Title I and Title III of federal regulations.

Note: Title I and Title III address the education of MLs in two distinct ways:

- Title I addresses issues of accountability and high-stakes testing.

- Title III provides us with a definition of the language instruction that multilingual learners must receive.

Serving Immigrant Students

It is important to note that all public and public charter school MLs have a legal right to free K-12 public education, regardless of their immigration status or that of their families.

Note: For additional information, please see the following:

- Immigrant Students' Legal Rights: An Overview (Colorín Colorado)

- Immigrant Students' Rights: A Guide for Schools' Front-Office Staff (Education Week)

Landmark Court Cases: Language Assistance Programs for Multilingual Learners

Many of the federal regulations about MLs are the result of lawsuits filed in local courts across our country and appealed to the United States Court of Appeals and the United States Supreme Court. These court cases addressed such critical issues as segregation, equal access to education, and the English language development and content learning needs of students.

- In 1973, Keyes v. Denver argued that groups of students were being segregated from their peers. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that schools must desegregate their students. This ruling meant that multilingual learners could not be segregated from their English-fluent peers.

- In 1974, Lau v. Nichols was a Supreme Court case brought on behalf of families of Chinese-speaking multilingual learners in San Francisco. They argued that the school district was not providing an effective (or even adequate) education because the children could not comprehend English. The court ruled that school districts must take steps to provide MLs with an instructional program that has equal access to education.

- In 1978, Castañeda v. Pickard argued that their local district was segregating students based on race and ethnicity and that the district failed to implement a successful bilingual education program for children to learn English. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that districts must establish a three-prong test to ensure that their educational program for multilingual learners is consistent with every student's right to an education.

The three prongs require educational programming for MLs to be:

1. Based on sound educational research

1. Based on sound educational research

2. Implemented with adequate commitment and resources

3. Evaluated and proven to be effective and that alternative evidence-based programming be implemented when it is not found to be effective.

Note: The Castañeda v. Pickard case is the most cited of all the court cases. For example, the Dear Colleague Letter references the first prong to describe common language assistance programs that are sound in theory. These include the examples on the following page.

Video: Castañeda v. Pickard: Are ELLs receiving the services they need?

Attorney Roger Rosenthal from the Migrant Legal Action Program explains the three-part test for sound education for ELLs in Castañeda v. Pickard case.

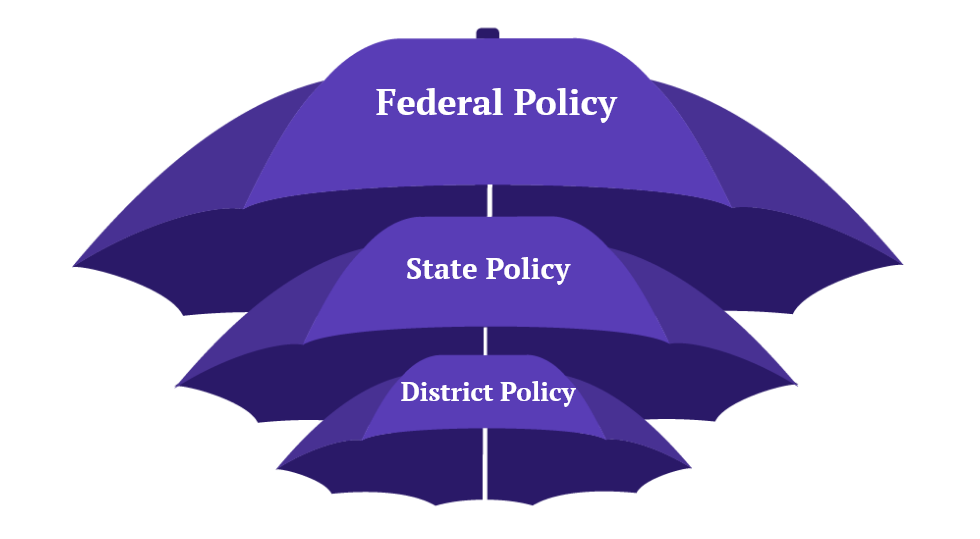

Safeguarding the Laws and Regulations

There are three governing agencies of public education: federal, state, and local agencies. Who has the most power? In the United States, federal education agencies are the most important and have the highest authority, followed by state education agencies and then local education agencies. Federal regulations take precedence over state and local education agencies. In turn, state regulations take precedence over local education policies. Lastly, all local education agencies, such as public-school districts and public charter districts, must follow their state's laws and regulations. Figure 1.2 illustrates the governing precedence of federal, state, and local education agencies (including the regulations regarding the education of multilingual learners).

Figure 1.2: Governing Precedence of Federal, State, and Local Education Agencies

According to federal laws, every local school district must provide MLs with instruction in English language development and simultaneously ensure that students are held to the same educational standards and outcomes as their English-fluent peers.

Following federal laws and regulations, each state education agency determines the assessments and language education instruction programs that will be followed by local education agencies. Following the three-prong test of Castañeda v. Pickard, these must be (1) based on sound research, (2) properly resourced, and (3) proven to be effective, and alternatives must be provided when they are not.

Note: The laws do not place restrictions on the amount of time that is needed for a multilingual learner to:

- Be able to listen, speak, read, and write in English.

- Be successful in classroom settings where English is the language of instruction.

- Be able to participate actively in his/her classroom, school, community, and beyond.

10 Compliance Issues and Solutions: Following the Laws

In January 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division and U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights sent a letter to every state education agency [SEA] and local education agency [LEA] (i.e., public school district and public charter school and district) in the nation. Known as the Dear Colleague Letter, the two federal agencies remind local schools and state education agencies of their legal obligation to ensure that MLs "participate meaningfully and equally in educational programs and services" (p. 2). The letter reflects the precedent court cases and federal Acts included in the timeline presented earlier (p. 2).

Our policy guide explains ten common compliance issues in public and public charter schools related to the education of MLs. It also offers strategies and actions steps for following the laws. (Note: For additional information, see the federal English Learner Toolkit).

These ten key issues, detailed in the rest of this guide, include the following:

- Identification and Assessment

- Language Assistance Programs

- Staffing and Staff Preparation

- Meaningful Participation in School Activities

- Avoiding Unnecessary Segregation

- Identifying and Serving Multilingual Learners with Disabilities

- Opting Out of Language Programs and Services

- Monitoring Students Who Have Exited Language Assistance Programs

- Evaluation of Language Assistance Programs

- Communication with Multilingual Families and Guardians

Add new comment